Women Led the Temperance Charge

Scroll to read more

Women Led the Temperance Charge

Temperance began in the early 1800s as a movement to limit drinking in the United States. The movement combined a concern for general social ills with religious sentiment and practical health considerations in a way that was appealing to many middle-class reformers. Women in particular were drawn to temperance in large numbers. Temperance reformers blamed “demon rum” for corrupting American culture and leading to violence, immorality and death.

The earliest temperance reformers were concerned with the overindulgence of American drinkers and encouraged moderation. By 1830, the average American older than 15 consumed at least seven gallons of alcohol a year. Alcohol abuse was rampant, and temperance advocates argued that it led to poverty and domestic violence. Some of these advocates were in fact former alcoholics themselves. In 1840, six alcoholics in Baltimore, Maryland, founded the Washingtonian Movement, one of the earliest precursors to Alcoholics Anonymous, which taught sobriety, or “teetotalism,” to its members. Teetotalism, so named for the idea of capital “T” total abstinence, emerged in this period and would become the dominant perspective of temperance advocates for the next century.

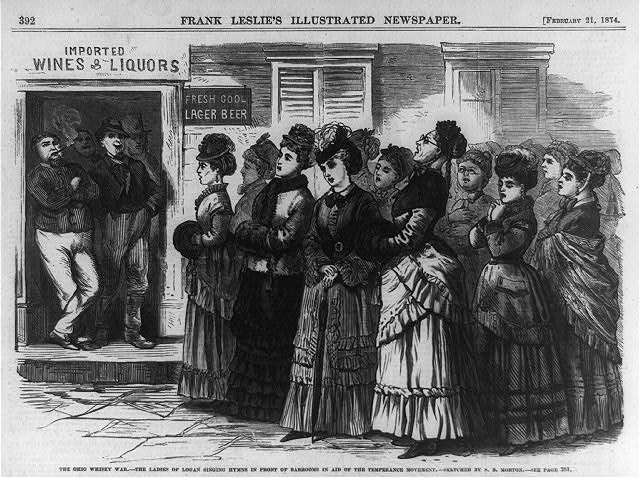

Women were active in the movement from the beginning. By 1831, there were 24 women’s organizations dedicated to temperance. It was an appealing cause because it sought to end a phenomenon that directly affected many women’s quality of life. Temperance was painted as a religious and moral duty that paired well with other feminine responsibilities. If total abstinence was achieved, the family, its home, its health and even its salvation would be secure. Women crusaders, particularly middle-class Protestants, pointed toward the Christian virtues of prudence, temperance and chastity, and encouraged people to practice these virtues by abstaining from alcohol.

The Civil War put an immediate, if temporary, end to early temperance efforts. States needed the tax revenue earned through alcohol sales, and many temperance reformers focused on bigger issues such as abolition or the health of soldiers. As the United States returned to life as usual in the 1870s, the next wave of temperance advocates set to work – this time with an aim at changing laws along with hearts. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was one such group.

The WCTU was founded in 1873, and it became a national social reform and lobbying organization the following year. Its second president, Frances Willard, helped to grow the WCTU into the largest women’s religious organization in the 19th century. Willard was known for her self-proclaimed “Do Everything” policy. She was concerned with temperance as well as women’s rights, suffrage and international social justice. She saw alcoholics as mentally weak and unstable, and believed temperance could help improve the quality of life of individual alcoholics as well as their families and communities.

Willard also saw the value of the WCTU for its ability to increase opportunities for women. The organization trained women in important skills for a changing world – leadership, public speaking and political thinking. The way she shaped the WCTU perfectly summarizes the multifaceted goals of the female-dominated temperance movement. By using temperance as a rallying cry, they sought to improve the lives of women on many different levels.

Willard was a strong president, but her “Do Everything” policy became the WCTU’s greatest downfall. By tackling so many issues, it made little concrete progress on alcohol reform. One exception was the influence it had on public education. In 1881, the WCTU began to lobby for legally mandated temperance instruction in schools. By 1901, federal law required “scientific temperance” instruction in all public schools, federal territories’ and military schools. These lessons were similar to the anti-drug programs that exist in schools today, but they perpetuated anti-drinking propaganda and misinformation. Lessons stressed that a person could become an alcoholic after just one drink and that most drinkers died because of alcohol. They also perpetuated racist stereotypes, including the belief that African Americans could not hold their liquor.

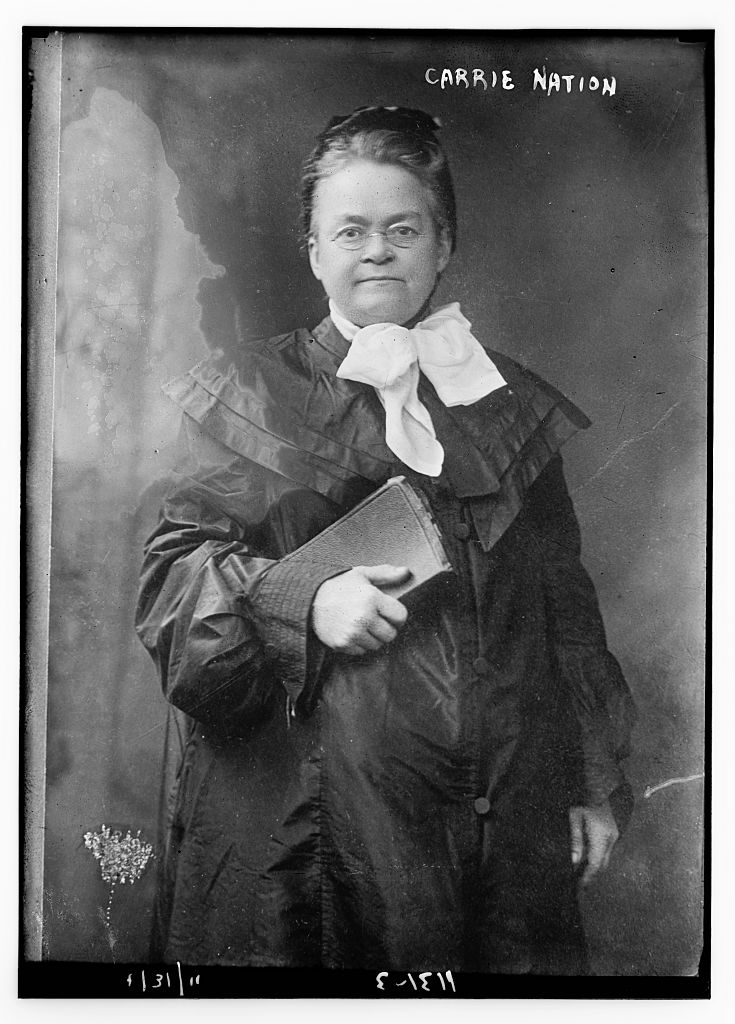

As the temperance movement waged on, advocates became more extremist, none more so than Carrie Nation. Nation’s first husband, a doctor in the Union army, was an alcoholic. They married in 1867 and had one daughter before separating, due in part to his alcoholism. Nation and her second husband settled in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, in 1889, where she was involved with the local WCTU chapter. At the time, Kansas was a dry state, but the law was generally not enforced. Nation believed something must be done, and in June 1900 she awoke from a dream in which God suggested that she go to Kiowa, Kansas, and break down a saloon. Nation did just that, and for the next 10 years she used axes, hammers and rocks to attack bars and pharmacies – smashing bottles and breaking up wooden furniture. She was arrested 30 times.

Nation referred to these attacks as “hatchetations,” and justified her destruction of private property by describing herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like.” One of the most radical components of Nation’s hatchetations was that she smashed pharmacies as well. She believed alcohol was evil regardless of use and thought the practice of prescribing alcohol for a host of ailments was as disturbing as the use of alcohol as a social lubricant.

Carrie Nation was a polarizing figure, but many people appreciated her actions and sent her gifts of hammers and hatchets. Companies also commemorated her efforts, and she sold souvenirs alongside her autobiography at lectures and other public appearances as she toured the country with her temperance message.

As the 20th century progressed, a final shift occurred in the Temperance Movement when groups such as the Anti-Saloon League began applying more political pressure and urging for state and federal legislation that would prohibit alcohol. As a shift toward legal action became the dominant approach to temperance, women, who still did not have the right to vote in most states, became less central to the movement. The early efforts of female temperance advocates no doubt shaped the movement, and the road to Prohibition was paved by their desire for a safer and healthier community.

Next Story: Speakeasies Were Prohibition’s Worst-Kept Secrets >