In Las Vegas, Prohibition Was Sporadically Enforced

Scroll to read more

In Las Vegas, Prohibition Was Sporadically Enforced

On Election Day in November 1918, Nevada voters considered a ballot measure known as the “Wet and Dry” question, asking whether to prohibit alcohol in the state. Earlier that year, Congress had passed the proposed 18th Amendment, for national prohibition, and sent it to the state legislatures for ratification. But Nevada was considering its state law first with the referendum. The dry side won with nearly 60 percent of the vote. In December, Nevada’s Supreme Court certified the state’s vote and prohibition became Nevada law as of midnight on December 17, 1918. As a result, the state went dry a month before the 36th state ratified the 18th Amendment on January 16, 1919.

Saloons across Nevada were ordered closed, including some historic ones from the 19th century in Reno. Most Nevadans then lived up north, and Reno was the state’s largest city. Down south in Las Vegas, Clark County Sheriff Sam Gay waited until after the holidays to issue a warning: “I am going to enforce the prohibition law to the letter. Mr. Bootlegger, this is your first and final notice from me. Your next notice will be a warrant for your arrest. All drugstore clerks should read this notice.”

But complicating the matter for law enforcers like Gay — and federal Prohibition agents – was the Nevada Legislature’s decision in 1923 to repeal the state’s four-year-old prohibition law. Since Nevada no longer had a prohibition statute, Gay and other police officers in the state were not technically duty bound to enforce national prohibition laws. Las Vegas did have a city ordinance against alcohol, but saloon owners operated openly, not like the underground “speakeasies” in other cities. A fine from a city violation or a federal Prohibition conviction was considered the cost of doing business.

So, after 1923, enforcement of Prohibition regulations in Las Vegas was more or less a federal matter, and local officers had the ready excuse of letting things slide. But Las Vegas would see many federal raids and investigations of illegal booze into the early 1930s. During Prohibition, Las Vegas would produce one flashy bootlegger, James Ferguson; its Mayor Fred Hesse was arrested for operating a still for two years to supply Ferguson; and the tale of ad-hoc Prohibition agent Ralph Kelly running an undercover operation in a fake speakeasy called Liberty’s Last Stand.

Las Vegas had 2,300 residents when national Prohibition took effect in 1920. The city was established in 1905 when a company building the Union Pacific Railroad from Salt Lake City to San Pedro, California, needed a station, repair yard, housing and businesses for its employees. To discourage the spread of intoxicating liquor among the residents, the company town confined alcohol sales to one square block, “Block 16,” a few blocks northeast of the railroad depot.

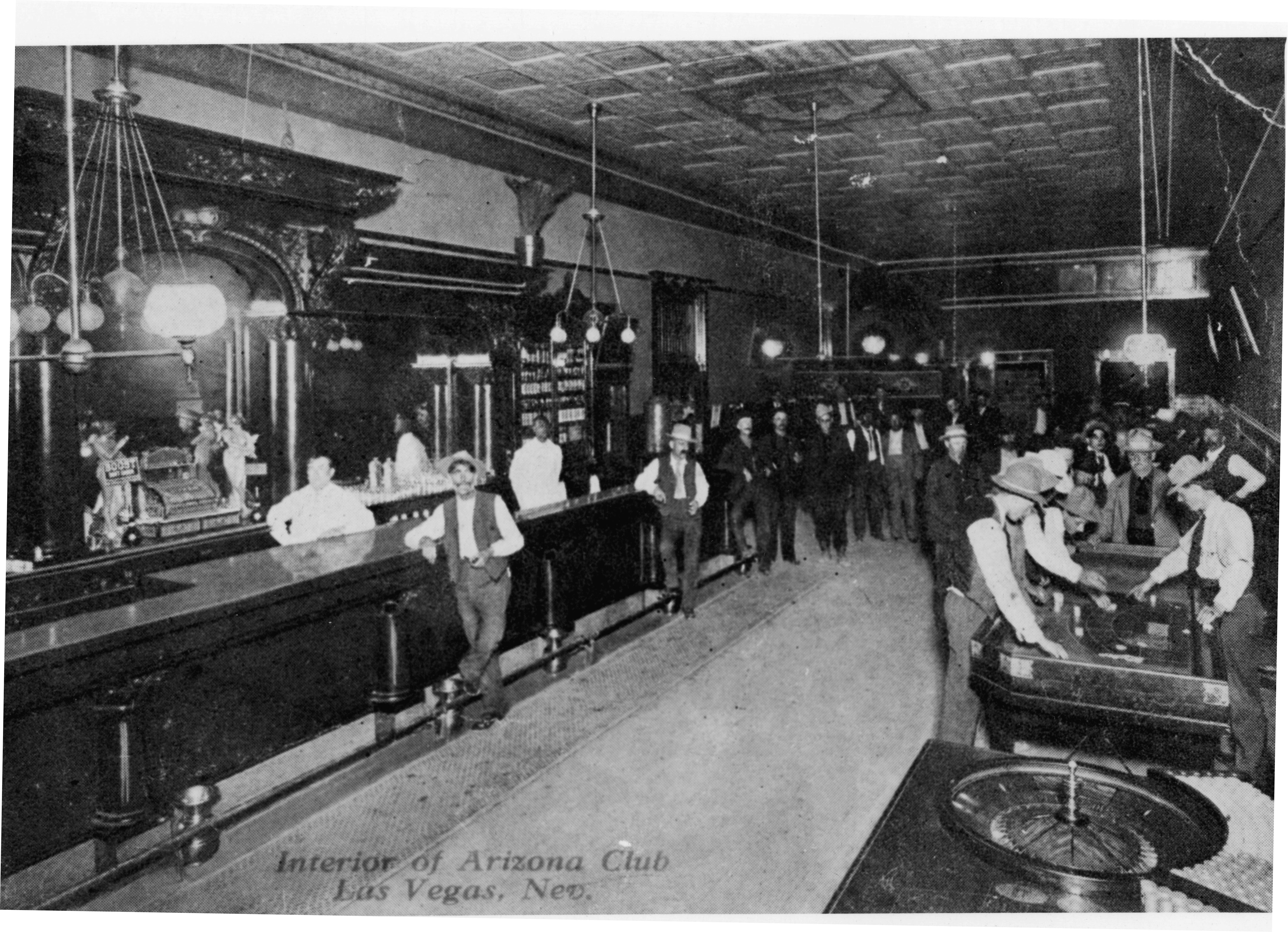

Early Las Vegas had a mixed experience with liquor. While the railroad company’s conservative managers opposed alcohol, they quietly conceded that booze provided economic activity from train passengers visiting a town surrounded by desert land that did not have much going for it beyond the railroad. Starting up first in canvas tents, then clapboard and brick buildings, a line of saloons on Block 16 included the Gem, Red Onion, Star, Arcade, Red Front and the finest in town, the Arizona Club. The bars were casually referred to as “resorts” because of the undisguised brothels inside where women serviced men in a number of small rooms known as “cribs.”

In early 1919, with Nevada’s state prohibition law already on the books, violations occurred in Las Vegas within weeks. In February, A.P. Chamberlain was the first convicted in town for having several bottles of liquor in his hotel room on Fremont Street. A local judge fined him $125, gave him a suspended sentence and ordered him to leave town and not return. On March 4, Sheriff Gay executed search warrants at the Arcade saloon and arrested three women after finding whiskey, vermouth, wine and brandy in their rooms and a man possessing 48 pints of whiskey. Two weeks later, in a show for the public covered by the Las Vegas Age, a local minister (appointed by a judge) stood on Fremont Street in the heart of downtown and ceremoniously poured out whiskey from about 10 bottles (seized from the raids) in front of what the Age described as “a large crowd of ‘uninterested’ spectators.”

“This is the first time in the history of the city that such a sight has been witnessed, and it being so unusual, pictures were taken of this occasion, which were very much in demand,” the Age reported.

Things progressed beyond petty offenses in January 1920 with the arrest of Lon Groesbeck, whom the Age described as the town’s “King of the Bootleggers” for bringing in whiskey “concealed in the false bottom of his car and other ways” and selling bottles from his room at the Northern Hotel on Fremont. Groesbeck was charged with having 23 pints of McBrayer brand America-made whiskey with U.S. government stamps from 1919, meaning the bottles were transported into the state. But amid allegations in the Age of Sheriff Gay’s “failure” to secure evidence of illegal alcohol in other recent bootlegging cases, District Attorney A.J. Stebenne, accompanied by two officers, himself raided Groesbeck’s hotel room, seized the bottles and put the man on house arrest.

What happened next to Groesbeck might have involved official corruption. On January 7, he pleaded guilty and a justice of the peace fined him, gave him 90 days in the county jail but suspended the sentence on the condition that he leave town. Stebenne refused to accept the suspension and at 2 p.m. that day took the case to District Court, where a judge reinstated the jail sentence. As the Age related, the judge’s order was handed to the first judge at 4 p.m., then to a sheriff’s deputy about an hour later. When the deputy arrived to pick up Groesbeck, the defendant and his car were gone. The Age lamented that his escape “is looked upon as a serious defeat of justice.”

Because of its small size and remote location, Las Vegas had no federal building, court or office space for Prohibition agents. The closest federal Prohibition agents were based in Los Angeles. Federal legal cases from Las Vegas were tried in U.S. District Court in the state’s capital, Carson City. But in November 1922, federal Prohibition agents from Los Angeles paid a visit to Las Vegas to arrest four men associated with Block 16 saloons on suspicion of illegal liquor sales. In 1923, Las Vegas police nabbed two men after recovering truckloads of beer and beer-making equipment in the basement of a downtown hotel. Federal agents returned in 1924 to arrest six locals for possessing whiskey and beer for sale and send them to Carson City to stand trial.

The laxity of Las Vegas law officers in enforcing Prohibition in its many saloons was apparent by the mid-’20s. The feds came to town again to make arrests in 1925. A U.S. marshal arrived from Carson City to pinch seven men and a woman on suspicion of selling liquor, and they padlocked (for one year) the doors to the Star, Nick’s Place, Jazz, Pastime, Colorado Club, Arizona Club, Lincoln, Arcade and Oxford Club saloons on Block 16.

Prohibition agents would uncover large-scale manufacturing of alcohol, likely to serve local customers and businesses. In 1926, agents working with deputy Prohibition administrator George Brady, based in San Francisco, arrested seven men in a series of raids, finding 850 gallons of whiskey and moonshine and four stills. One of the alleged bootleggers, R.C. McKay, had 350-gallon and 100-gallon stills on his ranch outside of town and 500 gallons of moonshine stored in his downtown home.

Federal raids targeting Las Vegas speakeasy operators intensified in the late ’20s. Most were charged with possession of alcohol for sale, conspiracy and maintaining a common nuisance. In early 1928, federal agents arrested proprietors of the Arcade, Star, Blue Lantern, Tip Deal’s Place, the Senate and the Pastime Dance Hall saloons. On the night of February 6, 1928, agents stormed the Arizona Club, Green Lantern, Honolulu Inn, Big Four, Miners Club, Jazz Bar, the Pastime and Double G. The 12 men and women arrested were permitted to plead guilty in local municipal court and together pay $4,800 in fines.

Those nabbed in the raid included an unusual pair – Las Vegas Mayor Fred Hesse and local bootlegger James Ferguson. Each faced serious charges of conspiracy to violate Prohibition laws for bootlegging. Hesse operated his own still to produce the alcohol. Ferguson was the more ostentatious of the two. He dressed in expensive clothing and drove around town in a yellow luxury car like a big shot. Hesse would escape jail, but not Ferguson.

In June, after two federal agents spent two weeks sampling illegal alcohol while posing as farmers on ranches outside Las Vegas, the feds pounced, took six men into custody, seized nine stills, more than 3,000 gallons of liquor mash, 300 cases of beer and a truck loaded with corn sugar.

By 1930, the feds stepped up enforcement of Prohibition amid national criticism and the transfer of its anti-liquor agents to the new Bureau of Prohibition in the Justice Department. In Nevada, support for Prohibition had fallen considerably. The magazine Literary Digest, which published public opinion polls on Prohibition, stated that its latest poll showed Nevada having the highest rate of opposition to Prohibition in the country.

Still, as a result of its switch from the Treasury Department to the Justice Department, the Prohibition Bureau made Las Vegas a higher priority for enforcement. Las Vegas was well-known for its unfettered illegal liquor sales. During 1931, the Prohibition Bureau subjected Las Vegas to the longest series of raids ever. A force of 23 agents from Los Angeles descended on January 9, 1931, to bust nine liquor joints based on an undercover operation. To show the importance of the raid, C. H. Seavers, administrator of Prohibition in California, Nevada and the Hawaiian Islands, came with them. Seavers told the Age that he intended to open a permanent enforcement office in Las Vegas with two agents.

Later, agents raided speakeasies, hotels and a service station, arrested 56 people and turned the Brown Derby bar “into a fingerprinting bureau,” the Age reported. In the largest seizure of alcohol in Las Vegas, agents recovered 4,000 bottles of liquor, 30,000 gallons of mash and arrested four men. They padlocked the Arizona Club and served arrests warrants or subpoenas on 20 people. The Age declared Las Vegas a “bone dry city” and “it is doubtful whether Southern Nevada will boast of the ‘wide open’ again during Prohibition.”

In February 1931, Special Agent Wayn Kain of the Justice Department in San Francisco traveled to Las Vegas to meet Ralph Kelly, a friend of a federal agent, to show him the illegal liquor spots around Las Vegas. As Kelly would relate later in a book, Kain told Kelly that construction of Boulder Dam project (30 miles from Las Vegas) “and the reported wide open conditions of the liquor traffic, were bringing Las Vegas nationwide reputation.” Kain said he was “anxious to get in on the publicity and that it would be a feather in his cap to have the credit for getting the facts and procuring the convictions.”

So started Kelly’s foray into working as an unofficial undercover agent for the Prohibition Bureau. Kelly took Kain on a short tour of Las Vegas bars and clubs, which operated in the open. One unsuspecting roadhouse owner told the men Nevada was the best state because “the Prohibition Department was powerless” there. The next day, Kain offered to pay Kelly a flat $900 and a future job to open up “a Wild West saloon” in town for the bureau to use to learn about the local liquor business. Kain also wanted to gather the names of officials taking payoffs from saloons and roadhouses. Kelly agreed. Kain then told him he wanted the saloon to be called “Liberty’s Last Stand” in order to generate publicity and attention.

Kelly, without letting on about his intentions, arranged to rent a small building on Stewart Avenue at Block 16 that was owned by W.W. “Bill” Cantrill, seen as “boss of the red light district” and whose “Fish and Shrimp” bar on the block had 10 rooms in the rear used by prostitutes and their managers.

They opened the bar on April 1, 1931, with two bartenders, who were kept in the dark about the operation. People crowded in right away. Kain – a pretty good drinker himself — directed Kelly to buy products from multiple liquor distributors to maximize arrests and pay them with bank checks to form a paper trail. Kelly easily bought whiskey, gin and absinthe, and he made a deal with the owner of a brewery. For evidence, Kelly poured samples into small bottles and labeled them. An investigator from San Francisco came in to collect the evidence.

Kain had a recording device then known as a Dictaphone installed in the bar’s back office (and linked to Kain’s hotel room) to pick up conversations with unknowing local government officials about graft. The stage was set. The local U.S. Commissioner W.H. Hooper in came in and asked for a payoff, and they got it on the Dictaphone. A saloon owner told them he was paying the chief of Las Vegas Police $100 a month for protection from the city ordinance. Within only three weeks, they figured they had evidence on 30 people. They sold Liberty’s Last Stand and prepared to make a raid on local bootleggers. The bureau assigned 55 agents from San Francisco, Reno and Los Angeles. Kelly and Kain bought another bar on Boulder Highway four miles from Las Vegas and ordered liquor delivered there from 12 dealers. As the dealers arrived in the morning, the 20 Prohibition agents with Kelly and Kain took in 35 suspects. The other 35 agents raided area saloons. In all, the agents made 108 arrests that day. The corrupt Commissioner Hooper worked on the security bonds for the suspects’ release. “This was by far the largest raid in Nevada,” Kelly wrote in his book. “The surprise was complete and action perfect.”

Many of the defendants pleaded guilty in Carson City and received prison sentences, other lighter sentences and fines. News of the big Las Vegas raid made headlines in newspapers and magazines, garnering the publicity Kain craved. Hooper was not arrested but resigned. Kelly later became a Prohibition agent in San Francisco, where his book, titled Liberty’s Last Stand, was published in 1932.

That same year, Las Vegas police investigated a brief “rum war” that erupted among rival bootleggers in Las Vegas, during which two people were killed and a “pineapple” bomb made of three sticks of dynamite blew up outside a planned new saloon near Block 16. Federal agents also made a number of raids in Boulder City.

In October 1933, with the repeal of Prohibition only weeks away, federal Judge Frank Norcross in Reno, who was about to leave to join the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, boasted that based on court records, Nevada led the nation in the enforcement of Prohibition. The judge said that 90 percent of arrests on Prohibition violations in the state resulted in convictions, that its rate of padlocking illegal clubs was 1,200 percent over the national average and that its rate of Prohibition enforcement was 100 percent to 1,000 percent higher than in other states. Kelly’s “Last Stand” may have had something to do with that.