Brewers and Distillers Found Creative Ways to Survive

Scroll to read more

Brewers and Distillers Found Creative Ways to Survive

When Prohibition took effect, thousands of American breweries, distilleries and vineyards found themselves in quite a predicament. Their previously legal operations were suddenly forced to adapt or die. Rather than shut down, many manufactured alternative products during the 13 years of Prohibition.

Dairy products were a common alternative for breweries, since they already owned massive refrigeration facilities. Yuengling, a Pottsville, Pennsylvania, brewer, opened a dairy best known for its ice cream. Pabst Brewing Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, made a processed cheese called Pabst-ett, selling more than eight million pounds during Prohibition. Kraft was so threatened by the Velveeta-esque product that it sued Pabst and won.

Coors, in Golden, Colorado, became the world’s largest supplier of malted milk, which it sold to soda fountains and candy companies. It also invested in the pottery business. The Coors Porcelain Company still makes ceramics and industrial products.

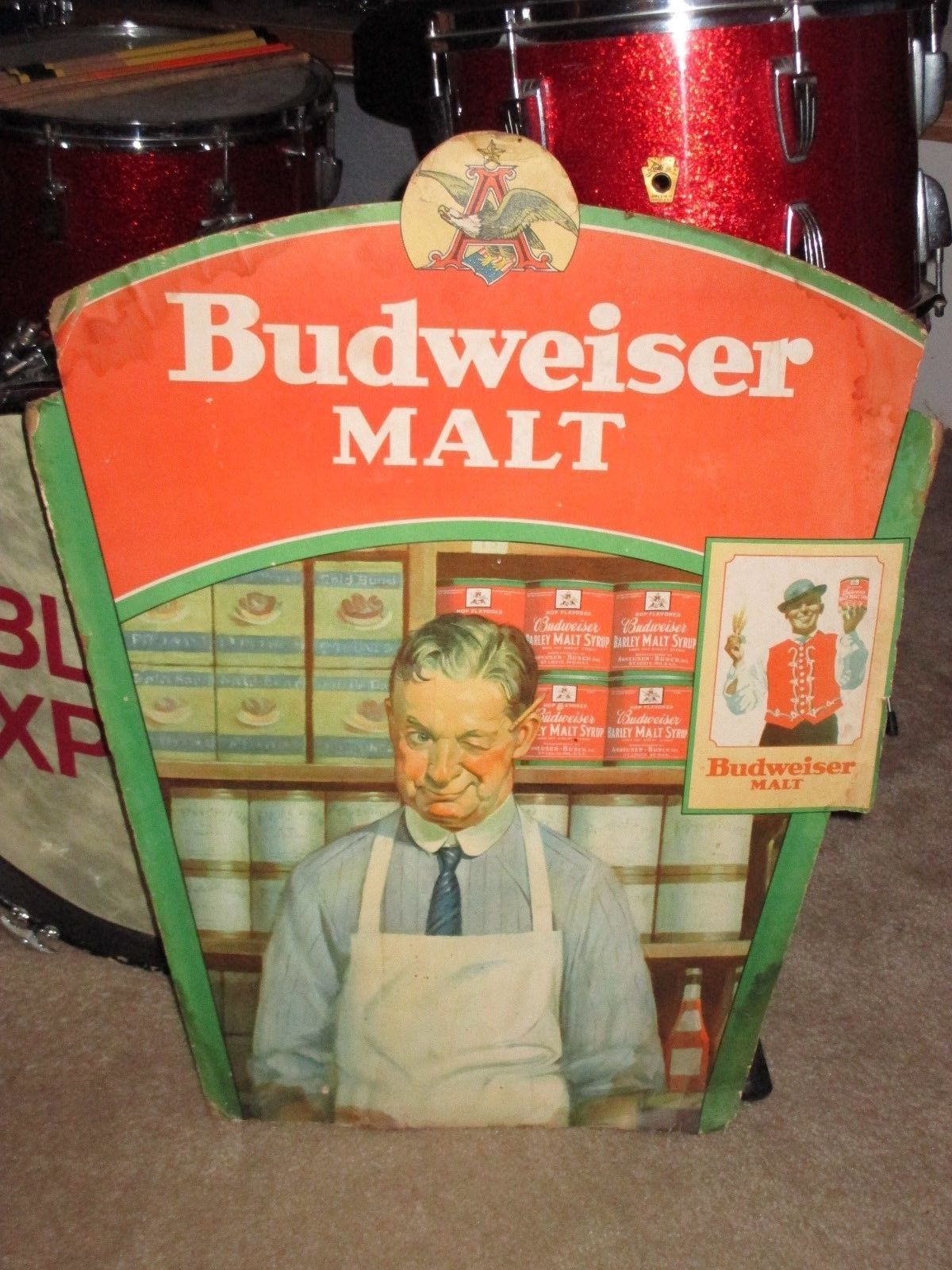

Anheuser Busch, whose Budweiser brand was the first nationally distributed beer, was one of the most innovative breweries. The St. Louis, Missouri-based company produced more than 25 different non-alcoholic products, including soft drinks, corn syrup, frozen egg products and truck bodies.

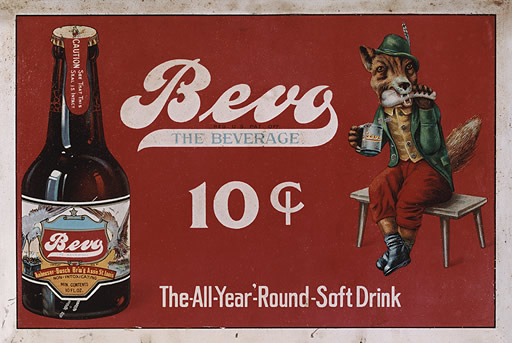

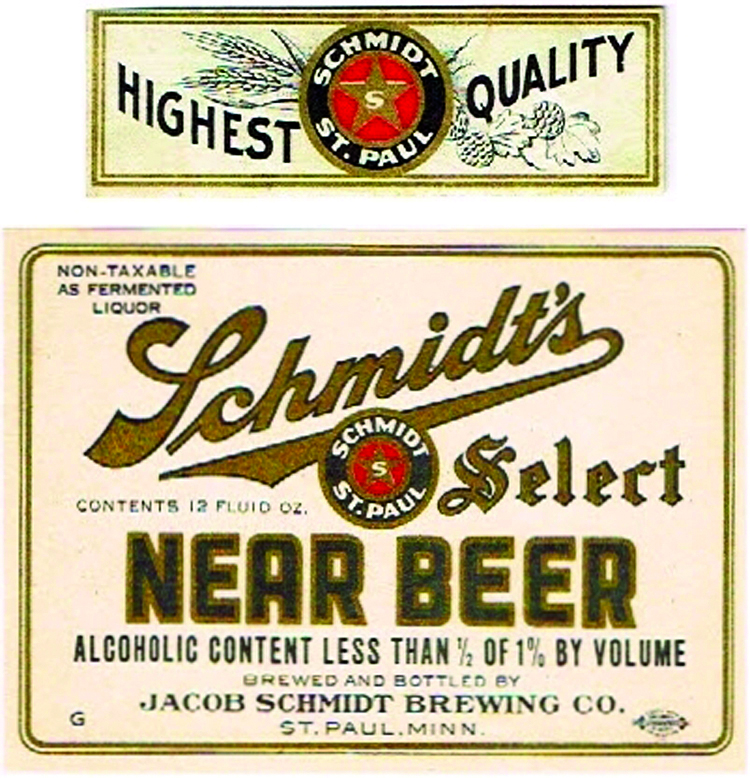

Regardless of the creativity of these products, most breweries survived by manufacturing things meant to replace or create beer. Anheuser Busch, Pabst and many others made “near-beer” with an alcohol content of 0.5 percent or less. Breweries also produced malt syrups and yeast, which when added to water and properly aged, produced a homebrew that could satisfy most any beer drinker.

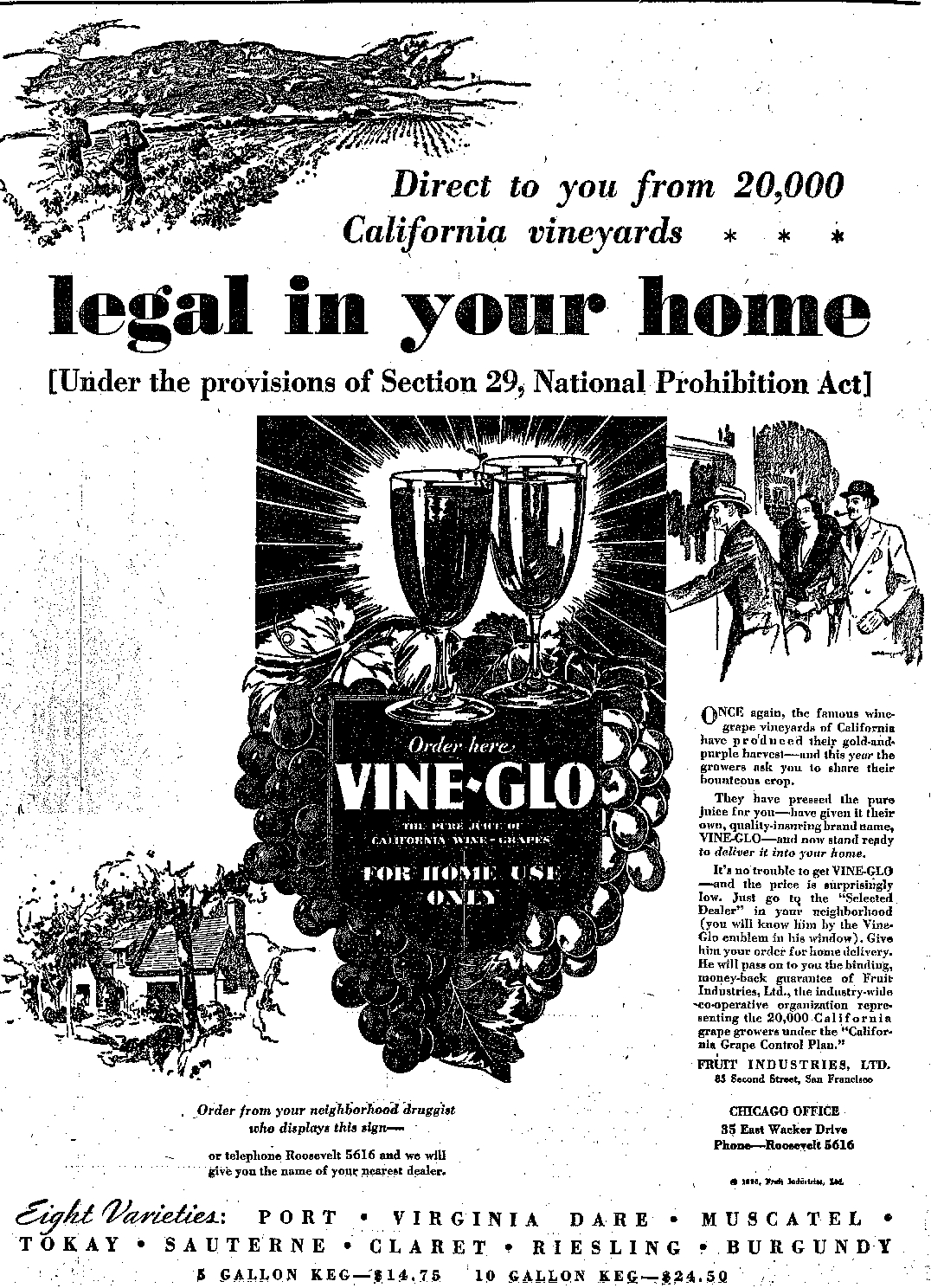

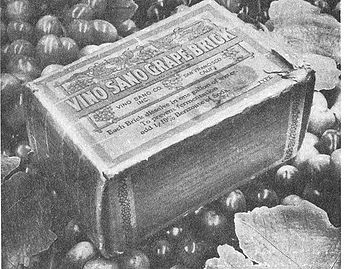

Vineyards also produced the ingredients necessary to make wine at home. Many California vineyards began producing “raisin cakes,” or dried grape bricks packaged with labels reading, “Caution: will ferment and turn into wine.”

Distilleries found it more difficult to convert their operations legally, but six distilleries stayed in business by registering for medicinal licenses. They were able to sell previously distilled whiskey and produce a limited quantity after 1930. Similarly, Anheuser Busch got permission to produce 55,000 barrels of real beer before Prohibition’s repeal, so that America would have something with which to celebrate.