Odd Facts and Stories from Prohibition

Scroll to read more

Odd Facts and Stories from Prohibition

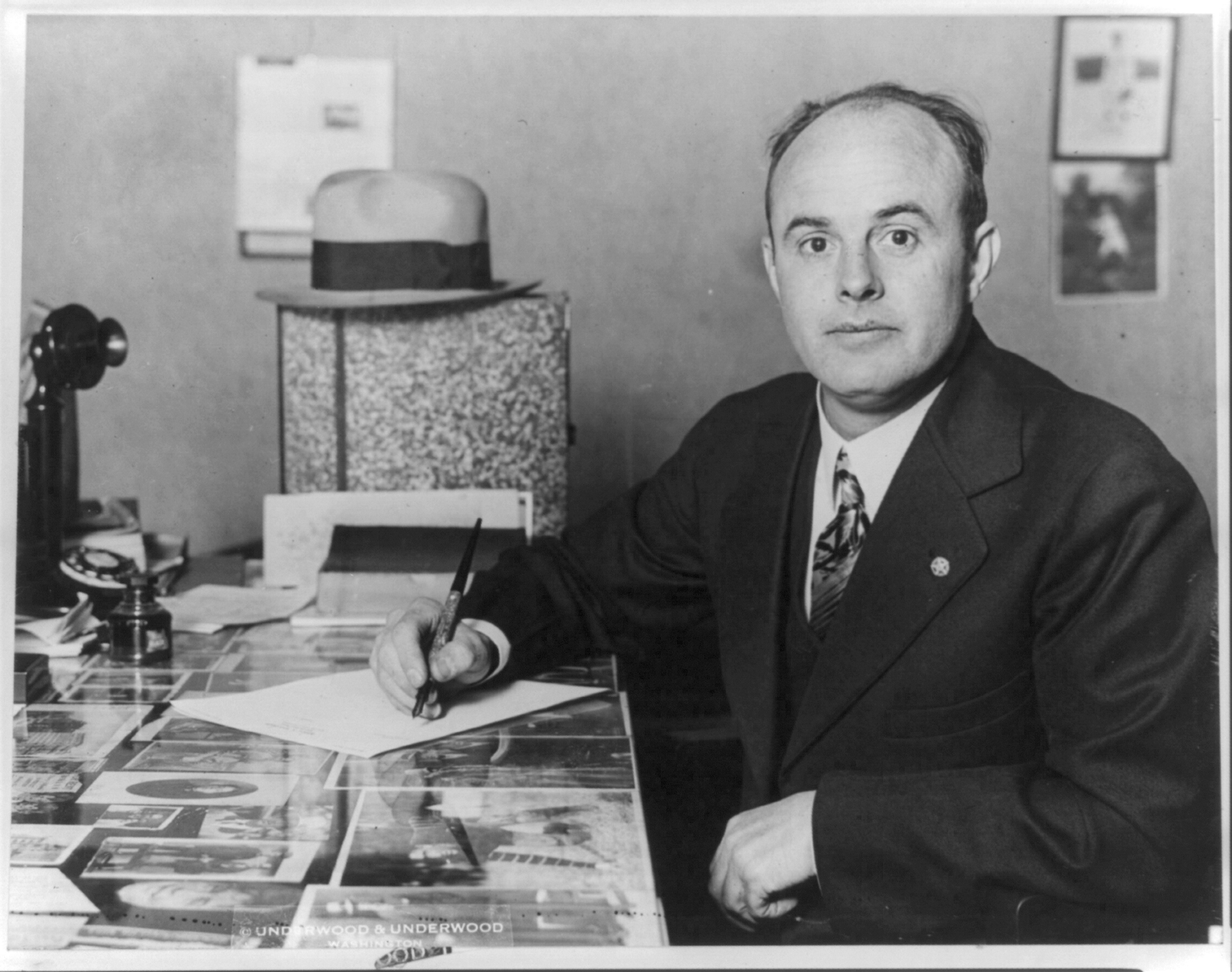

Congress had its own bootlegger known as the Man in the Green Hat.

Members of Congress who wanted alcohol during Prohibition could turn to Capitol Hill’s top bootlegger, George L. Cassiday. Cassiday walked through the halls of Congress making up to 25 deliveries of illegal booze a day while Capitol Police allowed him in at all hours. Over five years he supplied bottles of whiskey, moonshine, Scotch, bourbon and gin from a sturdy leather briefcase. His politician friends got him a room to work out of in the House Office Building. In 1925, when he was arrested while ferreting six quarts of whiskey to a House member, he had on a light green hat, and from press accounts the “Man in the Green Hat” stuck. Cassiday pleaded guilty and simply switched to selling in the Senate Office Building. His infamy spread to the office of Vice President Charles Curtis, who set up a sting operation in 1930 with a Prohibition agent “dry spy” watching Cassiday from the Senate’s stationery store. Cassiday was arrested with six bottles of gin and his client list (which was never published). He was sentenced to a year in prison. Cassiday later wrote that he helped 80 percent of Congress violate Prohibition laws.

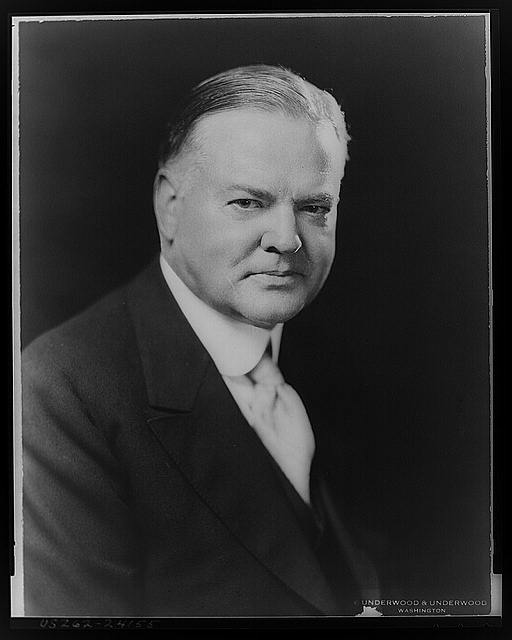

Herbert Hoover never referred to Prohibition as “a noble experiment.”

Many books and articles on Prohibition have quoted President Herbert Hoover describing Prohibition as “a noble experiment.” But Hoover himself complained that he was misquoted. Hoover was a confirmed supporter of Prohibition and campaigned for it the year he was elected president in 1928. He made this pro-dry statement at the Republican National Convention that year: “Our country has deliberately undertaken a great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far-reaching in purpose.” But years after leaving office, Hoover said he was misunderstood. “This phrase, ‘a great social experiment, noble in motive,’ was distorted into a ‘noble experiment,’ which of course was not at all what I said or intended to say. It was an unfortunate phrase because it could be turned into derision. Moreover, to regard the Prohibition law as an ‘experiment’ did not please the extreme drys, and to say it was ‘noble in motive’ did not please the extreme wets.”

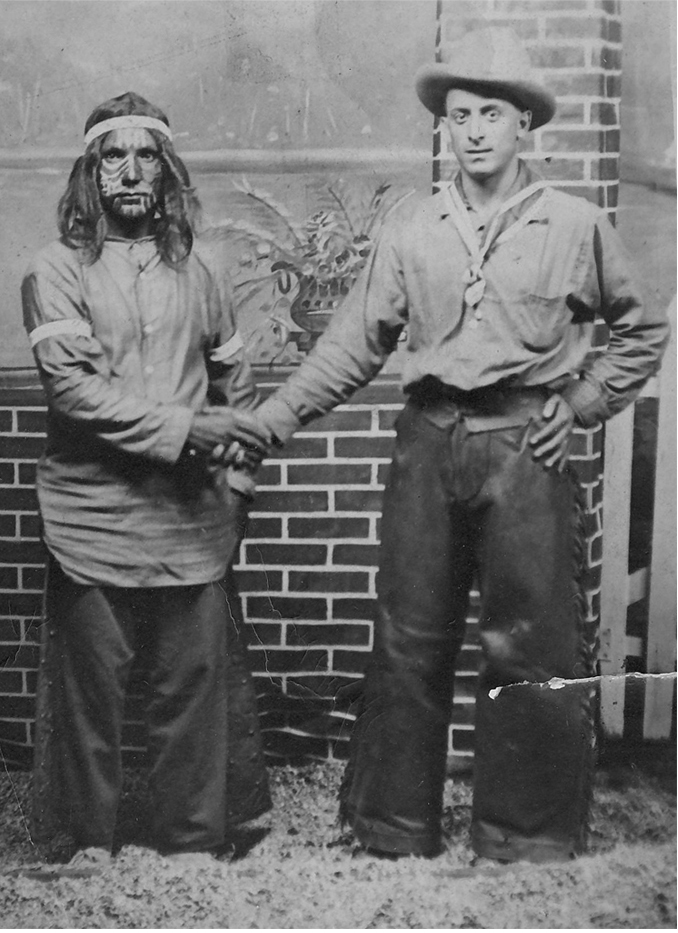

Al Capone’s oldest brother was a Prohibition enforcement agent.

While his younger brother Al built a criminal empire based on illegal liquor in Chicago in the 1920s, James Vincenzo Capone enforced Prohibition laws for the federal Indian Affairs administration on reservations of the Winnebago and Omaha tribes in Nebraska. Vincenzo, the eldest of the six Capone brothers, had changed his name to Richard Joseph Hart to hide his identity and in tribute to the silent movie cowboy, William S. Hart. After a stint in the circus, Vincenzo settled in the small town of Homer, Nebraska. He served as Homer’s town marshal, wore Western-style garb and hat and a pair of six guns that garnered him the nickname of “Two-Gun” Hart. With Indian Affairs in 1922, he was a special officer assigned to investigate bootlegging. While in Sioux City, Iowa, he killed a suspected bootlegger. He was charged with manslaughter but beat the rap. Later, while on another term as marshal of Homer, he lost his badge on suspicion of theft. He reunited with the Capone family in 1940, met his ailing brother Al in Miami and started receiving financial aid from them. He died in 1952.

The end of Prohibition made U.S. constitutional history.

The repeal of the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) by the 21st Amendment was the first and only time the Constitution was amended by state constitutional conventions – instead of state legislatures – and the only time an amendment abolished a previous one.

The Prohibition Party still exists.

Among the early organizations to support prohibiting alcohol in the United States was the Prohibition Party, formed in 1869 with the intent to elect politicians opposed to alcoholic beverages. The Prohibition Party remains America’s oldest third party. It was the first political party to permit women as members. Thomas Nast, the famed cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly in the late 1800s who created the elephant to symbolize the Republican Party and the donkey for Democrats, settled on the camel for the Prohibition Party, since that animal drinks only water. The Prohibition Party is today little more than a curiosity with very little support left. Its platform remains opposed to alcohol as well as tobacco. Its candidate for president of the United States in 2012 garnered just 519 votes nationwide. In 2016, the party nominated James Hedges of Iowa for president and Bill Bayes of New York for vice president.

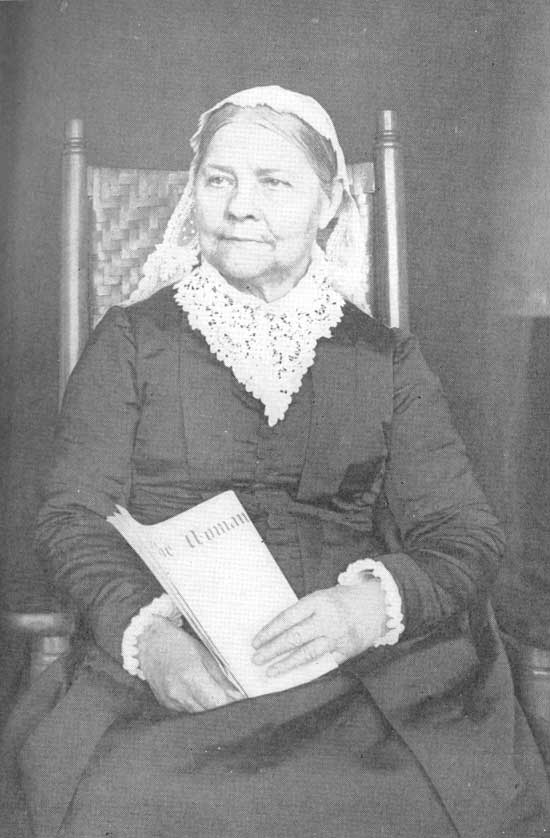

Some of the top leaders of women’s rights started out in the temperance movement that led to Prohibition.

Women’s rights activists of the 19th century such as Susan B. Anthony, Amanda Bloomer and Lucy Stone started out in the anti-alcohol, or temperance, movement. The unprecedented impact women had on the temperance movement led not only to Prohibition but to women’s suffrage. The drive that led to the 18th Amendment no doubt propelled the states, only a year after enacting Prohibition, to pass the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote nationally in 1920.

The term “speakeasy” did not originate during Prohibition.

It came from the two-word phrase “speak easy,” coined by American journalist Samuel Hudson back in 1889. Hudson, in his 1909 book Pennsylvania and Its Public Men, recalled that while in Pittsburgh in 1889, a new city liquor licensing law reduced the number of taverns there to only 96. That encouraged a rise in illegal bars all over town. Hudson asked Tim O’Leary, a local Democratic Party politician, to show him one. O’Leary explained that an elderly Irish widow who sold illegal beer and whiskey once warned her patrons, in her brogue, to “spake asy, now, the police are at the dure.” So, Hudson said, “Spake asy” became the moniker for the hundreds of unlicensed taverns in Pittsburgh. When Hudson returned home to Philadelphia, he wrote a column about the “speak easy” in the daily newspaper, The Item. “It is I who brought to Philadelphia and popularized the term ‘speak easy’ as applied to illicit liquor joints,” Hudson boasted in his book, published 11 years before Prohibition. “The term had an instantaneous success, being taken up by the people and police, and it has been in universal use ever since.”

Speakeasies often were located behind doors painted green.

During Prohibition, chances were that a door painted green meant it fronted a speakeasy. In Chicago, that tradition lives on with two of the town’s well-known bars dating from the 1920s. The Green Door Tavern on North Orleans Street is an Irish pub that opened in 1921 (a bar called The Drifter, also a former Prohibition speakeasy, is tucked away in the Green Door’s basement). On North Broadway, the famed Green Mill Cocktail Lounge once was a speakeasy part-owned by “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn of Al Capone’s Outfit. Capone, also a partner in the Green Mill, used to sit in a booth that is still inside the lounge. When comedian Joe E. Lewis refused to perform at the Green Mill in 1927, McGurn sent over three men who cut Lewis’ throat and face (he survived, and Capone paid for his medical work). McGurn was initially charged in the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre but he beat the rap due to lack of evidence.

In addition to fighting the ill effect of drunkenness, Prohibition supporters were motivated by a desire to derail political corruption.

One reason the Prohibition cause caught fire in America in the early 1900s was the public’s resentment over the spread and corrupting influence of the saloon. Indeed, the most powerful pro-Prohibition organization, founded in 1893, was the Anti-Saloon League. Tens of thousands of saloons, most of them in the country’s expanding urban areas, sold beer and liquor to almost anyone, including teenagers, and became influential in the community as meeting places for political and fraternal groups. The surplus of saloons made public drunkenness a common sight on city streets.

Saloons operated based on local political corruption. Owners leased bars to managers who might have to bribe city officials to get a license and police to avoid licensing problems. Major breweries – providing beer, the dominate drink in saloons — often owned many saloons, forcing managers to buy only their products. The liquor companies used their saloons as political meeting spots to deliver votes to candidates for political offices. To the communities around them, the ubiquitous saloons and the booze businesses supplying them represented the social and political scourges of alcohol. The “dry” movement sold the “prohibition” of manufacturing, transporting and selling alcohol as a way to eliminate the saloon, and the public pressured Congress and the states for it. Prohibition closed the saloons. Hundreds of breweries simply went out of business. Underground speakeasies – unlike saloons, friendly to female patrons — replaced them, but Prohibition put an end to the culture of the saloon that had dominated American city life.

In an age of segregation, Prohibition brought white and black patrons together in “black and tan” clubs.

In many parts of the United States in the 1920s, segregation of black and white was the rule, if not the law. But the peculiar circumstances of the Prohibition era challenged that. So-called “black and tans” referred to speakeasies and nightclubs where whites and blacks socialized and danced together as patrons. Ironically, Prohibition began right as jazz music was emerging as the pop music of America, mostly among the younger white set. In New York, the center of American jazz in the mid-’20s, many young whites went to the predominately black Harlem district to mingle and hear jazz performed by mostly African-American band members in small clubs. The same thing happened in the many jazz clubs on Chicago’s South Side. Dance crazes of the 1920s, such as the Charleston, Foxtrot, and Lindy Hop, were popularized by mostly the white crowd bopping to jazz music.

Among the more well-known “black and tan” clubs during Prohibition were Connie’s Inn (owned by bootlegger Conrad Immerman) and Small’s Paradise in New York, the Sunset Café (where jazz greats Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway played) in Chicago, and the Alhambra – renamed the Black and Tan in 1933 – on Jackson Street in Seattle. Other speakeasies for the wealthy, such as the Cotton Club, owned by bootlegger Owney Madden, in Harlem, had whites as patrons with African-Americans as jazz performers and service staff.

The term “black and tan” for an integrated bar or place did not originate in the 1920s but was in use decades earlier. American journalist and photographer Jacob Riis coined the phrase repeatedly in his 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives. Riis’s book chronicled the lives of impoverished people of various ethnic groups living in New York’s cramped and dirty tenements in the 1880s. “The borderland where the white and black races meet in common debauch, the aptly named black-and-tan saloon, has never been debatable ground from a moral standpoint. It has always been the worst of the desperately bad,” Riis wrote.