Queens of the Speakeasies

Scroll to read more

Queens of the Speakeasies

During Prohibition, no city had more illegal speakeasies than New York City, an estimated 32,000, most of them unattractive “clip joints” with cheap booze and suggestive women serving as shills to make men spend more. But three women who ran stylish nightclub-type speakeasies for the affluent crowd – Texas Guinan, Helen Morgan and Belle Livingstone — dominated New York’s nightlife from the mid-1920s to the early 1930s.

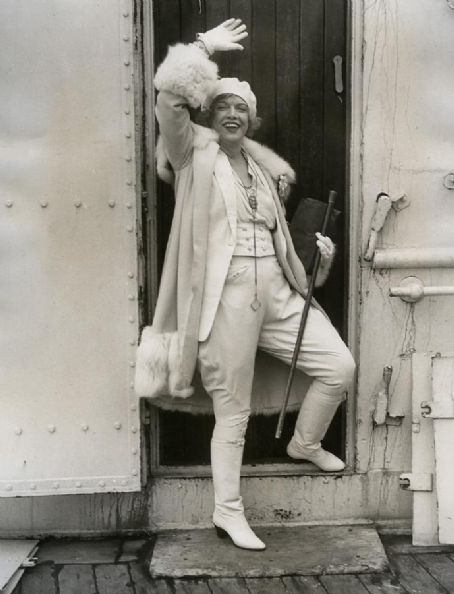

Texas Guinan: Speakeasy icon

Mary Louise Cecilia “Texas” Guinan, born in Waco, Texas, in 1884, was the first female Western movie star, a gun-slinging, bareback-riding cowgirl in three-dozen silent films in Hollywood (such as Two-Gun Girl and Lady of the Law). During Prohibition in 1922, New York show producer Nils Granlund introduced Texas to Larry Fay, a notorious rumrunner. She became the hostess and mistress of ceremonies at Fay’s El Fey club, one of the famed illegal speakeasies in New York. The club, on 46th Street near Broadway, opened from midnight to 5 a.m. It stood at the top of stairs leading to a door with a peephole. Inside, the silk-walled club seated about 80, with a small stage for chorus girls, including a young future film starlet, 14-year-old Ruby Keeler. Texas hired a young George Raft as a tap dancer.

At the El Fey, Texas originated a live bantering routine for patrons. Standing or seated in the middle of the club, she would greet customers with her line, “Hello, suckers!” She might lead everyone in a song, promise the crowd “a fight a night or your money back,” or crack, “You may be all the world to your mother, but you’re just a cover charge to me.” She referred to rich guys as “butter and egg men.” Her guests included celebrities of the day: Babe Ruth, Charles Lindbergh, Charles Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino, Clara Bow, Gloria Swanson, England’s Lord Mountbatten and Edward Prince of Wales, plus various gangsters and seedy types. Once during a raid, Texas is said to have had the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII)) don an apron and cook some eggs to pose as an innocent employee and prevent his arrest.

After authorities raided and closed the El Fey, Guinan and Fay opened Texas Guinan’s Club on West 48th Street, and when police closed it, they returned to the old location of the El Fey. She drank coffee, not alcohol. In 1925 she produced and starred in a vaudeville act, “Texas and Her Mob.” She left Fay (with the aid of mobster Owney Madden, who convinced Fay to let her be) and opened her own place, Texas Guinan’s 300 Club, on West 54th Street. She led a revue on Broadway called Padlocks of 1927 that fell flat with critics. Her company performed an irreverent song, “Oh, Mr. Buckner!” about Emory Buckner, the U.S. attorney of New York and enthusiastic prosecutor of speakeasy owners in the mid-1920s. She was arrested in 1927 at the 300 Club on suspicion of a Volstead violation. While at the police station, she sang the “Prisoner’s Song” before cops, Prohibition agents and reporters. At trial, she insisted she was only a hostess and a jury found her not guilty.

In 1929, Guinan played a character based on herself, a nightclub owner named “Texas Malone,” in a movie melodrama, an early talkie, Queen of the Night Clubs (the film footage is lost, but some of the audio survived). In 1933, months before her death, she was in the movie Broadway Through a Keyhole, in which the director showcased her bantering to customers as she did in her speakeasy days and delivering her “Hello, suckers!” line. She took a performing act, “Too Hot for Paris,” on a national tour to record crowds. But on November 4, 1933, while backstage after a show in Vancouver, she fell ill with ulcerative colitis and died the next day while undergoing surgery – exactly one month before Prohibition ended. Twelve thousand people attended her funeral in New York.

Helen Morgan: Torch singer

Helen Morgan was born in Canada in 1900. After her family moved to Illinois, she started her singing career at age 12. She was so small that she had to sit on a piano to be seen by the audience. At 18, she was crowned Miss Illinois, won $1,500 in a second beauty contest in Canada and moved to New York to study opera. Working as a singer in speakeasies during Prohibition, first in Chicago, Morgan made her breakthrough in 1924 in New York when show producer Billy Rose (associated with mobster Arnold Rothstein) had her headline in his classy speakeasy, the Backstage Club. She soon became famous for sitting atop a piano while singing “torch songs” about sad romances with men. She was cast in revues on Broadway, and in one, Americana, from 1926 to 1927, she sang the torchy “Nobody Wants Me” perched on a piano in the orchestra pit. Another huge break followed when she won the part of Julie in the debut on Broadway of the Florenz Ziegfeld-produced musical Show Boat in 1927.

At night after her Broadway shows, she continued to moonlight as a singer in speakeasies where she was a known draw. In one, the Chez Morgan, she fronted for a bootlegger in 1927. She was arrested in a raid but charges were dropped. She opened her own speakeasy that year, the Fifty-Fourth Street Club, at 231 West 54th Street, but the feds padlocked and closed it. In 1928, while at a new club, Helen Morgan’s Summer House, another arrest led to a trial but the jury acquitted her. More professional success followed. In 1929, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II (writers of Show Boat) wrote a Broadway show for her to star in, Sweet Adeline. She starred in the movie Applause that year and in Roadhouse Nights in 1930. Several records she recorded were national hits, such as “Why Was I Born?” and “Body and Soul.”

After Prohibition ended in 1933, Morgan’s career endured with performances on national network radio shows, starring roles in the movies Sweet Music in 1935 and Frankie and Johnnie in 1935 and a full sound movie version of Show Boat in 1936. But behind the scenes she battled alcoholism. In 1941, while on stage in Chicago performing in Scandals of 1942 (a version of which she played on Broadway in the 1920s), she collapsed and later died of liver and kidney aliments. She was 41.

Belle Livingstone: ‘Dangerous woman’

Belle Livingstone was born in rural Kansas sometime in 1875, when she was found abandoned while an infant. Named Isabel Graham, she moved with her foster parents to Chicago. In the 1890s, when her father opposed her joining a theater company, she proposed marriage to a paint salesman she just met, and then fled both her parents and new husband.

She adopted Belle Livingstone as a stage name. While in a show in New York, a publicist let it be known that Belle’s measurements matched those of the Gibson Girl, a pinup drawing idolized in the 1890s. Her photograph was published nationwide as the “ideal woman.” A New York writer said she had “poetic legs.” She knew Teddy Roosevelt, Diamond Jim Brady, Isadora Duncan and Lily Langtry. She performed in a Broadway show that traveled to London in the early 1900s, then ran her own “salon” in Paris. For her hourglass curves, a journalist called her “the most dangerous woman in Europe.” A self-described bohemian, Belle claimed to have had many affairs with prominent European men. She married three more times, to an Italian count, an English engineer and a wealthy Cleveland man.

In 1927, at age 52, after a long, comfortable life in Paris but with little money, Belle returned to New York. It was the Prohibition era. Friends took her to a speakeasy hosted by Texas Guinan. Belle hatched an idea for a “super-speakeasy” for New York’s upper crust, with a $200 annual membership. An investor, Franklin Berwin, financed it. She secured a house on East 52nd Street. It was her first speakeasy in Manhattan. She had Guinan over and they became close friends. But she could not meet her bills and it folded. In 1929 she moved to 384 Park Avenue to start the Silver Room, but federal agents raided it. She located her third and finest club in a five-story house at 126 E. 58th Street. This time, she asked gangster and rival speakeasy owner Owney Madden if it was all right with him. “Lady, go as far as you like,” she recalled him saying in her 1959 autobiography.

Belle dubbed her new speakeasy the Fifth-Eighth Street Country Club. Her pre-screened members included “celebrities, near-celebrities, social registries and financial barons.” It had vaulted Florentine ceilings, Italian marble floors, an indoor miniature golf range, a brook stocked with goldfish, rooms with ping pong tables and backgammon games and a lounge with a long wooden bar. Guests took off their shoes to enter an Oriental-themed room of large paintings, draperies and stain floor pillows.

She sent out invitations for opening night October 25, 1930, and some surprise guests came by: Archduke Leopold from Russia, the Duke of Manchester from England and John D. Rockefeller. Others were not invited but came by anyway. A staffer ran to inform her that Chicago Mob boss Al Capone was sitting in the Monkey Room with others. “We don’t pass anyone who isn’t right” Belle quipped to Capone. He replied, “At least we’re not federals.” Madden also showed up. The group drank nonalcoholic drinks. She sent a check for $1,000 to the table to see what would happen, and the bill was fully paid, with a $100 tip for the waiter. The opening made her a bundle. A reporter for the Evening World wrote, “Can it be that Belle is going to push Texas out of the spotlight?”

But within weeks, the feds raided her again. She famously tried to escape arrest while wearing red silk pajamas. Nabbed and charged with Volstead violations, she kept the Country Club open until January 1931, when a judge sentenced her to 30 days in New York’s Harlem jail. Once out, she used her considerable earnings to open speakeasies in Nevada, California and Texas but could not beat the local hoods at the game. In 1933, while back in New York, she learned of Guinan’s death and helped prepare her friend’s corpse for the funeral. For Belle’s own remains, she arranged for a monument in a graveyard in France with the epitaph: “This is the only stone I have left unturned.” She died in 1957 at age 82.