The Speakeasies of the 1920s

Scroll to read more

Speakeasies Were Prohibition’s Worst-Kept Secrets

When Prohibition took effect on January 17, 1920, many thousands of formerly legal saloons across the country catering only to men closed down. People wanting to drink had to buy liquor from licensed druggists for “medicinal” purposes, clergymen for “religious” reasons or illegal sellers known as bootleggers. Another option was to enter private, unlicensed barrooms, nicknamed “speakeasies” for how low you had to speak the “password” to gain entry so as not to be overheard by law enforcement.

The result of Prohibition was a major and permanent shift in American social life. The illicit bars, also referred to as “blind pigs” and “gin joints,” multiplied, especially in urban areas. They ranged from fancy clubs with jazz bands and ballroom dance floors to dingy backrooms, basements and rooms inside apartments. No longer segregated from drinking together, men and women reveled in speakeasies and another Prohibition-created venue, the house party. Restaurants offering booze targeted women, uncomfortable sitting at a bar, with table service. Italian-American speakeasy owners sparked widespread interest in Italian food by serving it with wine.

Organized criminals quickly seized on the opportunity to exploit the new lucrative criminal racket of speakeasies and clubs and welcomed women in as patrons. In fact, organized crime in America exploded because of bootlegging. Al Capone, leader of the Chicago Outfit, made an estimated $60 million a year supplying illegal beer and hard liquor to thousands of speakeasies he controlled in the late 1920s.

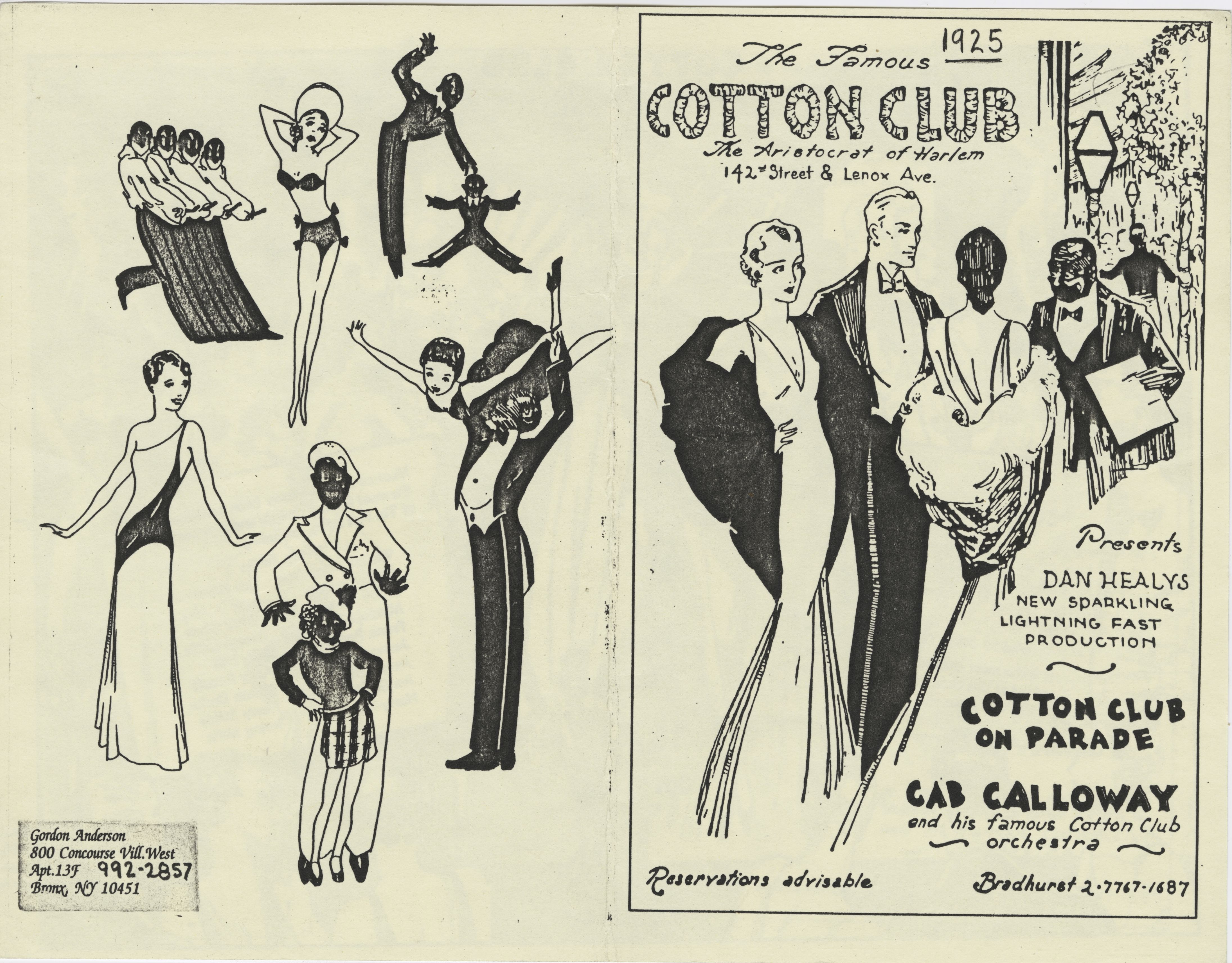

The competition for patrons in speakeasies created a demand for live entertainment. The already-popular jazz music, and the dances it inspired in speakeasies and clubs, fit into the era’s raucous, party mood. With thousands of underground clubs, and the prevalence of jazz bands, liquor-infused partying grew during the “Roaring Twenties,” when the term “dating” – young singles meeting without parental supervision — was first introduced.

Speakeasies were generally ill-kept secrets, and owners exploited low-paid police officers with payoffs to look the other way, enjoy a regular drink or tip them off about planned raids by federal Prohibition agents. Bootleggers who supplied the private bars would add water to good whiskey, gin and other liquors to sell larger quantities. Others resorted to selling still-produced moonshine or industrial alcohol, wood or grain alcohol, even poisonous chemicals such as carbolic acid. The bad stuff, such as “Smoke” made of pure wood alcohol, killed or maimed thousands of drinkers. To hide the taste of poorly distilled whiskey and “bathtub” gin, speakeasies offered to combine alcohol with ginger ale, Coca-Cola, sugar, mint, lemon, fruit juices and other flavorings, promoting the enduring mixed drink, or “cocktail,” in the process.

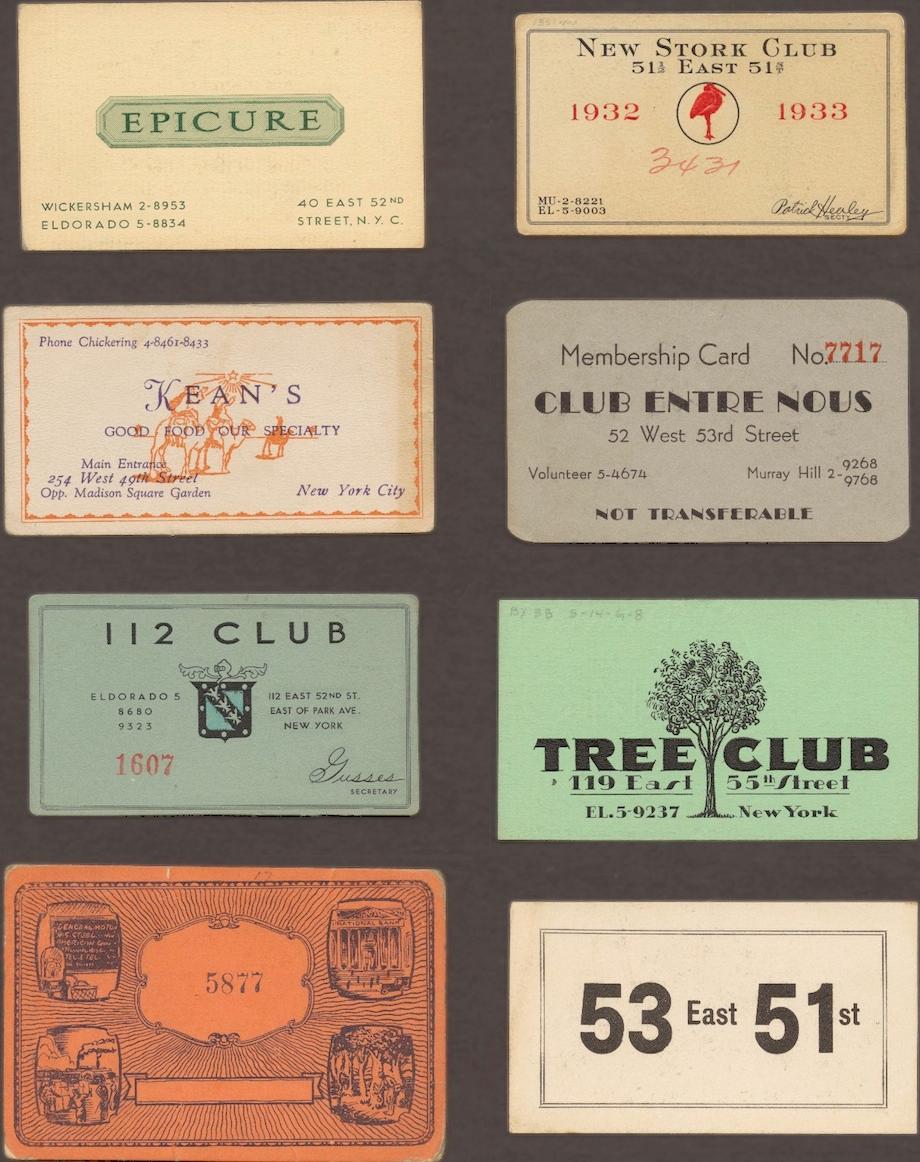

As bootlegging enriched criminals throughout America, New York became America’s center for organized crime, with bosses such as Salvatore Maranzano, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello. At the height of Prohibition in the late 1920s, there were 32,000 speakeasies in New York alone. The most famous of them included former bootlegger Sherman Billingsley’s fashionable Stork Club on West 58th Street, the Puncheon Club on West 49th favored by celebrity writers such as Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley, the Club Intime next to the famous Polly Adler brothel in Midtown, Chumley’s in the West Village and dives such as O’Leary’s in the Bowery. Harlem, the city’s black district, had its “hooch joints” inside apartments and the famed Cotton Club, owned by mobster Owney Madden, on 142nd Street.

Owners of speakeasies, not their drinking customers, ran afoul of the federal liquor law, the Volstead Act. They often went to great lengths to hide their stashes of liquor to avoid confiscation – or use as evidence at trial — by police or federal agents during raids. At the 21 Club on 21 West 52nd (where the Puncheon moved in 1930), the owners had the architect build a custom camouflaged door, a secret wine cellar behind a false wall and a bar that with the push of a button would drop liquor bottles down a shoot to crash and drain into the cellar.

Near the end of the Prohibition Era, the prevalence of speakeasies, the brutality of organized criminal gangs vying to control the liquor racket, the unemployment and need for tax revenue that followed the market crash on Wall Street in 1929, all contributed to America’s wariness about the 18th Amendment. With its repeal via the 21st Amendment in 1933 came an end to the carefree speakeasy and the beginning of licensed barrooms, far lower in number, where liquor is subject to federal regulation and taxes.