The Remnants of Prohibition

Scroll to read more

The Remnants of Prohibition

National Prohibition ended on December 5, 1933, with passage of the 21st Amendment. But while prohibition was repealed at the federal level, state and local restrictions on liquor continue to this day.

Section 2 of the 21st Amendment allowed the states to write their own laws governing alcohol. It states that the “transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.” Subsequent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court agreed that each state could regulate the sale of alcohol within its borders.

Today, Prohibition’s legacy is a collection of archaic and unusual liquor laws that vary from state to state, county to county, city to city, town to town. Some states kept prohibition alive for some time after 1933, with Mississippi the last to hold onto it until 1966. For decades following repeal some states had so-called “blue laws” on liquor until relatively recently. In 2002, 16 states repealed laws banning alcohol sales on Sundays.

Still, in more than a few jurisdictions, alcohol prohibition still exists. About 16 million Americans live in areas where buying liquor is forbidden. Dozens of “dry” counties in the United States – or “moist,” with some of their cities wet – remain today, mainly in the Midwestern and Southern Christian “Bible Belt.”

Many states permit counties and cities to decide for themselves, by local vote or ordinance, whether to be “wet” or “dry.” In Kentucky, 31 of its 120 counties are dry, where selling or possessing booze is a “class B” misdemeanor. Thirty-seven of Arkansas’ 75 counties are dry. In Alabama, 24 of 67 counties are dry, with all but one having at least one “wet” city. In Texas, voters in 450 dry municipalities voted to become “wet” between 2004 and 2012, leaving 126 where you still can’t buy alcohol. In Nevada, the small town of Panaca is the state’s only dry jurisdiction.

Some states allow beer to be sold but not with more than 3.2 percent alcohol content (such as Utah), or a maximum of 6 percent content (West Virginia), even as high as 17.5 percent (South Carolina). Many states cap the alcohol levels in wines sold (in Vermont, consumers may buy wines with less than 16 percent alcohol at supermarkets). Some states, such as Alaska, do not permit alcohol sales in grocery stores. Twelve states still prohibit the sale of spirits (beer and wine are exempted) on Sundays. Indiana doesn’t allow any alcohol to be sold on Sundays. Some don’t allow sales of beverages on major holidays. Kansas bans it on Memorial Day, Labor Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter.

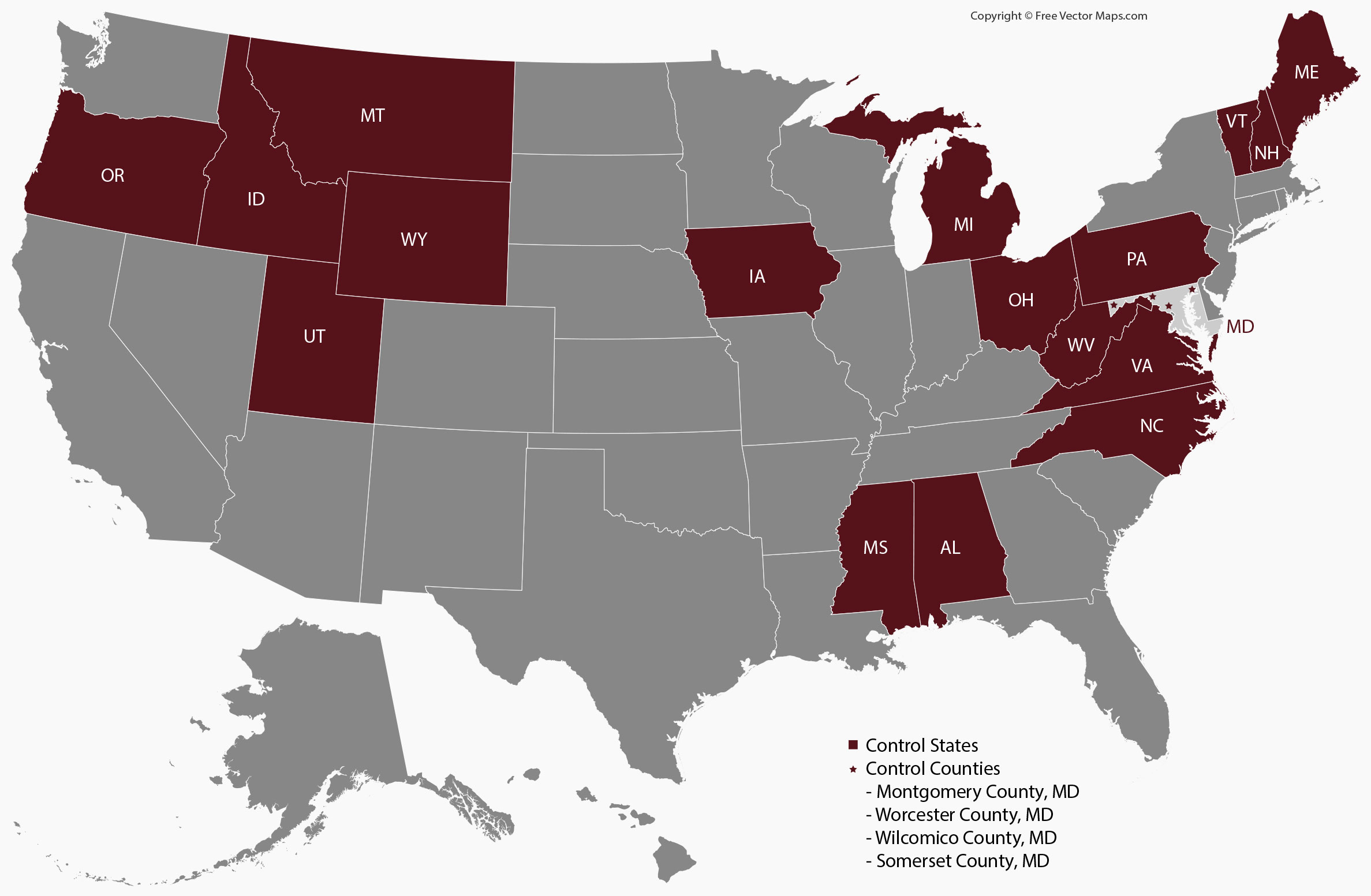

Also, there are 18 states with Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC) laws, regulating the wholesale or retail sales of alcohol, except for beer and wine. Some ABC states sell state-produced spirits to independent stores and some only will sell liquor from state-owned stores with limited hours of operation.

One state with a unique history with Prohibition after national repeal is Oklahoma. The state repealed Prohibition only in 1959, but kept strict limitations. Beer above 3.2 percent alcohol content, or “high point beer,” is categorized as liquor and may be sold only at room temperature in state-regulated liquor stores. The same went for wine. In 1984, the state finally granted its counties the option to sell liquor by the drink in bars and nightclubs. Later, the state relaxed some laws. Wineries are allowed to sell wine on site. In 2016, the state permitted small “craft” beer breweries to sell their brews with alcohol content higher than 3.2 percent on site without having to use a wholesaler. While four other states also have the 3.2 percent beer law, Oklahoma accounts for about 50 percent of the nation’s sales of 3.2 beer.

The variety of state laws shows not only that the Prohibition era has had a lasting effect on society but that people still disagree about regulating alcoholic beverages. Every state has specific laws at least specifying the age people may buy alcohol, hours and locations where alcohol may be sold, the kind of licenses required to sell alcohol in bars, stores, restaurants and to manufacture and transport beer, wine and hard liquor (distilled spirits such as whiskey, vodka and gin).

While it’s legal today to make wine and beer at home for personal or family use, running an old-fashioned “still” to concoct spirits or making gin in a bathtub remain felony crimes under federal law. The U.S. government since the end of Prohibition has legal jurisdiction and oversight over the manufacturing of liquor intended for sale. Owners of breweries, wineries and hard liquor-making distilleries seeking to sell their wares must obtain a federal permit from the U.S. Treasury Department before making anything, and then pay federal taxes on every gallon they produce. States, counties and cities also set their own taxes on liquor sales.

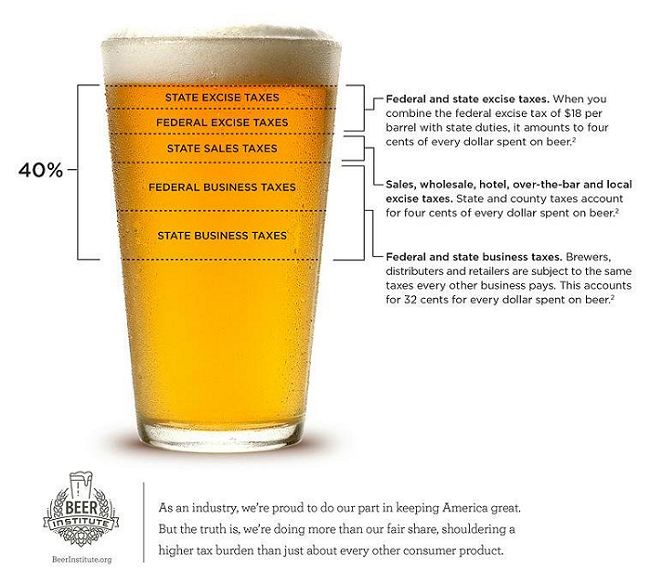

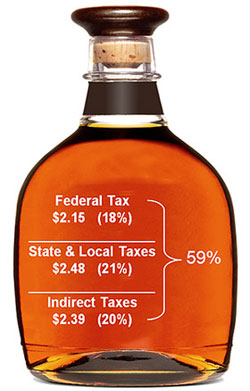

In fact, liquor taxes are an important source of government revenue. The industry is among the highest taxed in the country along with tobacco. The federal tax is $7 to $18 per barrel for beer, $1 to $3.40 per gallon for wine and $13.50 per proof gallon of spirits. The combination of federal, state and local taxes adds a hefty premium to the price of a bottle of alcohol. In Chicago, for instance, the tax rate on a 750-milliliter bottle of distilled liquor (such as vodka), including federal, state, city and county taxes, plus state and local sales taxes, would amount to 28 percent.

In 2014, the U.S. government levied $7.9 billion in federal excise taxes on liquor, which by federal estimates is a $400 billion to $500 billion per year industry employing about four million people. The states received about $6.1 billion in alcohol taxes that year.

Another legacy of Prohibition is that Americans are drinking less. Before Prohibition began in 1920, the average American drank 2.6 gallons of alcohol each year. That average, even with speakeasies and the bootlegged liquor, dropped by more than 70 percent in the early years of Prohibition. After its repeal, Americans did not return to the pre-Prohibition drinking level until 1973. Since the mid-1980s, annual consumption has fallen to about 2.2 gallons per person. The United States does not even make the list of the top ten countries with the highest consumption of liquor. Number one is the small nation of Luxembourg, at 4.11 gallons per capita, then Ireland at 3.62 gallons and Hungary with 3.59 gallons.