The Rise of Jazz and Jukeboxes

Scroll to read more

The Rise of Jazz and Jukeboxes

While jazz music predated Prohibition, the new federal law restricting liquor advanced the future of jazz by creating a nationwide underground nightclub culture in the 1920s. This competitive club culture had mobsters such as Al and Ralph Capone of Chicago and Owney Madden of New York vying for the best performers for their drink-swilling customers. That culture advanced the careers of major jazz performers such as Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Paul Whiteman, Bix Beiderbecke and jazz itself as an art form. It also would lead to millions in profits for organized crime bosses.

Prohibition forced tens of thousands of saloons throughout the country to shut down, but the demand for drink remained, and thousands of illegal bars, or speakeasies, soon opened. Gangsters, who manufactured or transported liquor in violation of the federal Volstead Act, supplied the liquor, owned the speakeasies, or both. At first some speakeasy owners offered live music by bands linked to vaudeville stage acts. But jazz was a better fit for the era’s party mood. Bar owners soon were hiring small jazz bands with local players to furnish background or dance music.

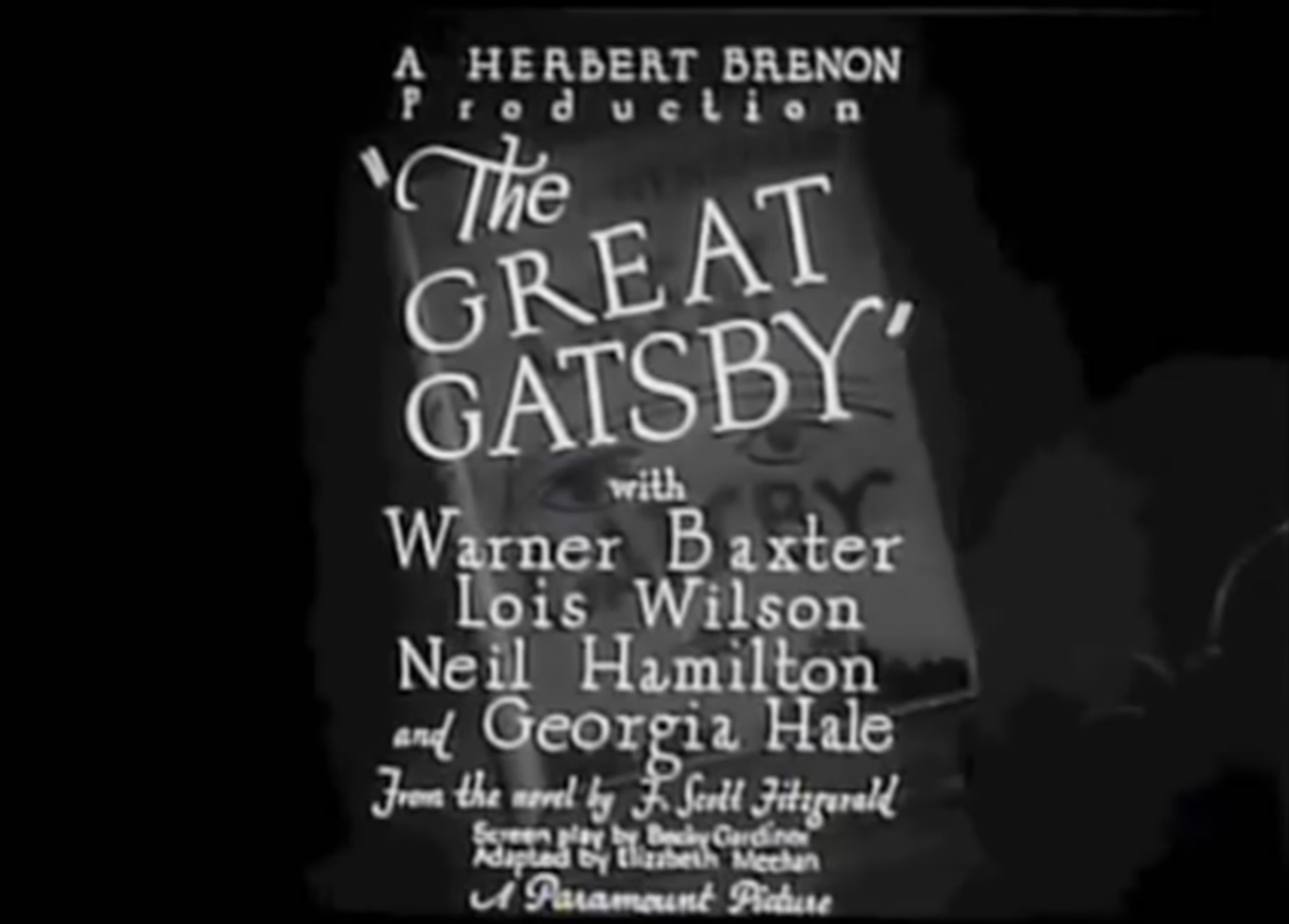

The decade that F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of the 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, hailed as “the Jazz Age” began when jazz was already the pop music of its time, especially among members of the younger generation in the 1920s. Women, given the right to vote by the 19th Amendment, were welcomed in the new underground lounges. Many young women rebelled against the restrictions on “ladylike” behavior and dress of the Victorian age, becoming liberated “flappers” or what Fitzgerald would call “good-time girls.” The combination of jazz and liquor-infused partying by men and women characterized this period known as the “Roaring Twenties,” inspiring dance crazes such as the “Charleston,” “Fox Trot,” “Shimmy,” “Toddle” and “Lindy Hop.”

Recordings of jazz and blues music had been sold as “race records” since 1917 and played on acoustic phonographs, both home models and the coin-operated variety in arcades. In 1920, Prohibition’s first year, Bessie Smith, a rising African-American jazz singer, sold one million records. Also that year, the first commercial radio stations went on the air. Soon, the popularity of jazz soared as more records were cut, top musicians performed in clubs in New York and Chicago and the music was broadcast on the airwaves. Within two years, more than 550 licensed radio stations operated across the nation.

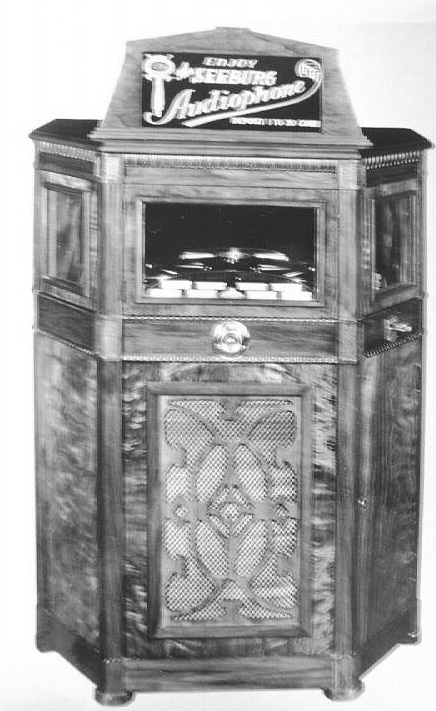

Other technological advances would spur the growth of jazz during Prohibition. Coin-run phonographs playing low-fidelity acoustic records operated alongside louder, coin-run player pianos and band instrument machines as cheap entertainment in speakeasies. But coin-operated phonographs (known a decade later as “jukeboxes”) would take over with the introduction of 78 rpm records made with amplified electronic sound in 1926. The American Music Instrument Company of Michigan introduced the first “coin-op” electronic record machine, with ten 78 records and 20 song selections, in 1927. The new cultural phenomenon of listening to jazz on high-fidelity 78 rpm records on a nickel-per-play machine became a fast hit in speakeasies.

The marquee nightclubs serving liquor in New York and Chicago – known to police but frequently tolerated thanks to payoffs from club owners – became larger, noisier and more opulent as they competed for paying customers. Armstrong and Ellington were among the jazz acts in highest demand. Two of the best-known nightclubs of the era were Madden’s Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, owned by Conrad Immerman, both in New York’s predominantly black Harlem district (Connie’s Inn closed its doors with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933).

The new opportunities for live musicians in higher-paying clubs would foster two types of jazz in the 1920s. From New Orleans, where Armstrong and Oliver originated, came a style in which musicians performed together as an ensemble. In Chicago, a free-form, improvisational style arose. Armstrong, who moved with Oliver to Chicago in 1922, became a big success as a jazz recording artist, as did Smith, who recorded 180 songs during the decade. Some of their jazz records openly referred to illegal booze. One of Smith’s songs, called “Me and My Gin,” included the refrain, “Any bootlegger sure is a pal of mine.” Armstrong recorded a popular song about drinking titled “Knockin’ a Jug.”

Many Prohibition-era jazz players were African-Americans who often performed for exclusively white audiences. But the illicit club culture would go on to promote integration, leading to what were known as “black and tan” clubs with multiracial crowds. This Prohibition-inspired trend was nearly unprecedented for an age in America when segregation was not only the cultural norm but a common government policy.

As Armstrong, Oliver, Ellington and many top black jazz musicians attained national fame in the 1920s, they felt pressure from Mob-owned clubs. Some mobsters used enforcers to threaten players into signing performing contracts or extorted money from them. White jazz artists who also won national reputations during the era included Whiteman, a band leader nicknamed the “King of Jazz,” and Beiderbecke, the hard-drinking cornetist, pianist and recording artist.

By the late ’20s, Chicago was regarded as America’s jazz capital with its famous line of clubs on the city’s South Side. Its most infamous bootlegger of hard liquor and beer was Al Capone, leader of the crime syndicate known as the Outfit. Capone himself at one time owned 10,000 speakeasies in the city. He liked jazz and installed his brother, Ralph, to run their finest nightclub, the Cotton Club, in the Chicago suburb of Cicero. The club served white audiences and dignitaries such as Chicago Mayor Jim “Big Bill” Thompson. Al instructed Ralph to book only black musicians because he considered them as oppressed as his Italian immigrant relatives.

The devotion to jazz shown by the Capone brothers and other business-minded mobsters during Prohibition would benefit black jazz greats Armstrong, Ellington, Waller, Earl “Fatha” Hines and Ethel Waters, and with them, the future of jazz as an enduring genre of American music.