Prohibition Agents Lacked Training, Numbers to Battle Bootleggers

Scroll to read more

Prohibition Agents Lacked Training, Numbers to Battle Bootleggers

In January 1919, two-thirds of America’s state legislatures officially approved the 18th Amendment, banning the manufacture, sale and distribution of liquor. Prohibition was set to begin one year later, on January 17, 1920.

But the new constitutional amendment did not specify how the law would be enforced, so Congress passed a separate law, the National Prohibition Act. The law was also known as the Volstead Act, named after Congressman Andrew John Volstead of Minnesota, a prohibition supporter who guided the bill as chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

While the 18th Amendment was only a few pages long, the Volstead Act took up 17 pages singled spaced in Congress’ legislative record for 1919. In language that some found confusing, the act called for the commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service (in the Treasury Department) to oversee enforcement and make adjustments to the regulations as needed. The IRS subsequently established the Prohibition Unit, staffed by agents who were not required to take Civil Service exams, leaving the door open for members of Congress and local pols to appoint their cronies, including applicants with questionable backgrounds. The government provided funds for only 1,500 agents at first to enforce Prohibition across the country. They were issued guns and given access to vehicles, but many had little or no training.

Effective enforcement of Volstead was almost doomed from the start. The country’s 48 states at the time were not inclined to help much, preferring to have federal agents shoulder the burden. Available operating funds were inadequate – the federal government and states together spent less than $500,000 to enforce Prohibition in 1923.

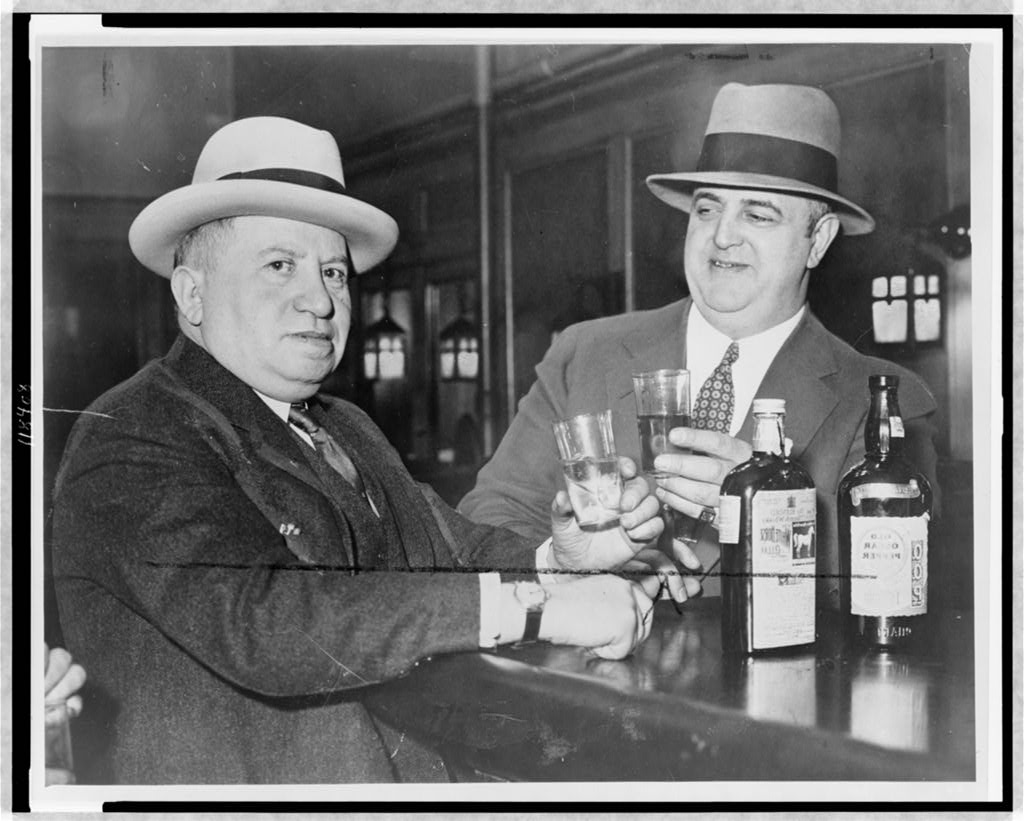

Prohibition agents and cooperative local law enforcers throughout the country seized warehouses full of whiskey, busted up stills, smashed countless bottles of liquor, took axes to beer barrels and dumped the contents into gutters and sewers. Their brethren in the Coast Guard, after a slow start in the early ’20s, used speed boats and retired military ships to pursue, board and seize the vessels of rumrunners smuggling liquor into the country on the Great Lakes, the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

The escapades of Prohibition officers – nicknamed “Prohis” (pro-hees) — were covered in newspapers and magazines, on radio and in movie theater newsreels. Some attained national fame. Early on, the biggest Prohi stars were Isidore “Izzy” Einstein and Moe Smith, known as “Izzy and Moe,” in New York City. Not only were Izzy and Moe truthful and law-abiding, they took their jobs to a level no one could match.

Izzy, a rotund, 5-foot, 5-inch Austrian Jewish immigrant and former postal worker, was a wiz at foreign languages. He spoke German and three other tongues, knew words in Russian, Spanish, French, Italian and Chinese, and could imitate foreign accents in English. He also played the violin. To bust violators of Volstead, Izzy dressed as a woman, a Texas oil man, a Southern colonel, a football player in a muddy uniform or a horse wagon driver, then he might fake the accent of his choice to create a diversion. He would go up to a speakeasy, innocently order a legal “near-beer,” then ask for a pint of illegal whiskey from the unsuspecting barkeep, and upon receiving one say, “There’s sad news here. You’re under arrest.” Izzy, “the man of a thousand disguises,” arrested more than 4,900 people, sometimes as many as 30 in a night.

Izzy one day convinced his friend Moe, a cigar store owner and small-time boxing manager who was flabbier than Izzy, to join him as a Prohibition agent. The pair soon went on scores of “undercover” capers without anyone discovering their tricks until it was too late. Working together they posed as everything from firemen to farmers, gas meter inspectors, street cleaners, gravediggers and truck drivers. One of their two-man shows in New York was for Moe to masquerade as an out-of-towner and Izzy as his loudmouthed sidekick. While at a restaurant, Izzy would quietly tell the waiter his traveling friend was looking for some liquor, then arrest the server when he produced it. They also arrested bootleggers who obtained wine meant for Jewish sacraments and for industrial alcohol sold for manufacturing tobacco. They even blackened their faces to raid a deli in the African-American district of Harlem.

They used a device Izzy invented, a rubber hose hidden in a small coat pocket leading to a flask sewn into another pocket. They would buy a bottle of illegal liquor at a speakeasy and discretely pour the contents into the hose, catching the liquor for use as evidence, then arrest the seller. Izzy never packed a gun, but Moe did, although he never fired it at anyone. Some speakeasy owners posted press pictures of Izzy on the wall with the message, “Look out for his man.” Though famous, Izzy took even to posing as himself. He would ask a bartender to sell him a pint of whiskey and say, “I’m Izzy Einstein,” which the barkeep would laughingly repeat to his patrons. After the barman produced the liquor, Izzy would arrest him.

Izzy and Moe traveled and made arrests in cities such as New Orleans, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Cleveland. In Hollywood, California, they dressed in suits of armor as “extras” for a movie set in medieval times to enter and bust a speakeasy used by actors. But the pair’s more straight-laced superiors in the Prohibition Unit complained about the publicity they generated and dissolved their partnership “for the good” of the unit in 1925. While Izzy and Moe were the most famous, there were other agents whose actions garnered them nicknames in the press – M. T. Gonzaulles, known as “the Lone Wolf of Texas,” Daisy Simpson, “the Woman of a Hundred Disguises,” and Al “Wallpaper” Wolff.

As the years went by, what Prohibition agents and state and local police found daunting to enforce would evolve into a virtually impossible task later, even after the feds expanded to 3,000 agents late in the era. First was the sheer scope of the challenge. Prohibition agents were tasked with keeping watch for bootleggers on the country’s 12,000 miles of shoreline, as well as the borders with Canada and Mexico that reached close to 3,900 miles. The unit received assistance from the U.S. Coast Guard on seas and lakes and Customs and Immigration agents at borders, but they still could not keep up with bootleggers. Agents had to police the 170 million gallons of industrial alcohol – exempted by Volstead – produced in the national annually, tens of thousands of commercial stills making spirits and potentially 22 million American households able to churn out home-fermented wine, beer and hard liquor.

Yet another challenge was greed in the ranks of agents. Their salaries ranged from only $1,200 to $3,000 per year. Many agents could not resist the opportunity to accept payoffs from cash-rich bootleggers. As early as the end of 1921, the Prohibition Unit terminated 100 of its agents in New York alone for taking bribes after issuing permits to obtain legal alcohol. Some had direct ties to bootleggers or were bootleggers themselves. Making the jobs of honest Prohis harder were the many local police officers who took payoffs from bootleggers in exchange for looking the other way and tipping them off about federal raids.

With so many Prohis tainted by graft, and Al Capone having his way with the liquor rackets in Chicago, the Hoover administration shook things up in what would be a two-pronged attack on bootleggers, using Volstead and federal tax laws. In 1927, Elmer Irey, the head of the Enforcement Branch of the then-named Bureau of Internal Revenue, started investigating criminal evasion of federal incomes taxes by Capone and other booze runners. The U.S. Supreme had ruled in May of that year that a bootlegger, Manly Sullivan, could not claim income from illegal activity was untaxable, nor that to file a federal tax return on income earned from criminal acts would violate his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. Irey created a Special Intelligence Unit of revenue agents, led by Frank Wilson, to go after bootleggers for tax evasion and money laundering in the nation’s hotbed for illegal liquor, Chicago. Capone controlled 20,000 speakeasies and employed 1,000 hoodlums. There were 300 Prohibition agents in Chicago.

In 1930, the Prohibition Unit was transferred from Treasury to the Justice Department and renamed the Bureau of Prohibition. The increase in violent crime investigated by Prohibition agents had exceeded Treasury’s core duty of collecting taxes, and Justice was better suited to probe organized crime. George E.Q. Johnson, the U.S. attorney in Chicago, took charge of overseeing the efforts by Irey and Wilson to get Capone on criminal tax charges and those of the Bureau’s new investigative chief in Chicago, Special Agent in Charge Eliot Ness. A 26-year-old graduate of the University of Chicago, Ness was assigned to coordinate a special detail of Prohis to take on Capone’s liquor rackets and build criminal cases against him for Volstead Act violations. Ness handpicked nine of the bureau’s best agents, all under age 30, whom he determined were incorruptible and uniquely skillful (later dramatized in the TV series and movie, “The Untouchables,” based on Ness’ ghost-written memoir). Ness used his special unit to take aim at Capone’s breweries, but learned early that he could not trust the Chicago police. While planning a raid on a brewery, he informed Chicago’s finest and an officer on Capone’s dole informed the Mob boss. Ness brought reporters along to a building to view the raid, but was embarrassed to see there was no illegal liquor inside. He kept information on subsequent raids to within his special unit.

But the new Bureau of Prohibition had a lot to answer for. By 1930, 1,587 out of 17,816 federal Prohibition employees had been fired for everything from lying on their applications to perjury, robbery, bribery, embezzlement and contempt of court. Critics of Volstead complained that the corruption resulted because the law exempted Prohibition agents from Civil Service rules. Volstead’s advocates contended that Congress might not have passed the law without the exemption.

Many Prohi agents, however, did their jobs on the up and up. As John Kobler wrote in his 1973 book Ardent Spirits, for most of Prohibition, from 1920 to 1930, agents took about 577,000 suspects into custody, and prosecutors won convictions from almost two in three. Agents confiscated 1.6 million stills and other liquor-making devices, 9 million gallons of hard liquor, one billion gallons of malt liquor, a billion gallons of wine, hard cider and mash, plus 45,000 cars and 1,300 boats. The value of the property federal agents seized was set at $40 million ($550 million in 2016 dollars), and state and local officials likely seized about the same amount. But the caseload for arrestees on liquor charges overburdened the court system and most suspected bootleggers pleaded guilty to reduced charges in exchange for lighter sentences and fines.

In the meantime, Irey’s Intelligence Unit started obtaining convictions and prison sentences for tax evasion against some of Chicago’s liquor racketeers, first Terry Druggan and Frank Lake, then Al’s brother Ralph Capone, who got three years in prison in 1929.

It took longer for Wilson and his agents to crack the case against Al Capone. By mid-1930, they had reviewed 1.7 million financial documents thought related to the gangster’s rackets, which aside from liquor included gambling and brothels. Then Wilson happened on three ledgers showing illegal gambling profits to Al Capone, Ralph Capone and others in Cicero, a suburb of Chicago, from 1924 to 1926. Wilson tracked down the man who wrote some of the entries in the ledgers, Leslie Shumway, and convinced him to testify before a grand jury against Al in March 1931. On June 5, the panel indicted Capone on more than 20 counts of evading taxes — on $123,000 in income in 1924 and about $1 million (a small percentage of his actual income) from 1925 to 1929.

The following week, the grand jury considered evidence in cases Ness and his special unit pursued on alleged Volstead violations against Capone. The jury returned indictments on 69 people, including Capone, based on 5,000 counts. The case was based mainly on Capone’s $13 million brewery business. Before going to trial, prosecutors decided to keep the Volstead charges in reserve in favor of the tax evasion case, thinking a jury might be less inclined to convict Capone for bootlegging than for cheating on his taxes.

They were right about the tax charges. The jury at Capone’s 1931 trial found him guilty on five of the counts. The judge sentenced Capone to up to 11 years in prison and made him pay a record $50,000 in fines. Capone’s gang continued to run his rackets while he sat in prison, but they lost their main source of income with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Capone served time in a number of federal prisons, including Alcatraz, until his release in 1939. He died of a brain hemorrhage in 1947.

After the demise of Prohibition, the Bureau was changed to the Alcohol Beverage Unit, under the supervision of J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. But then the agency was sent back to Treasury to handle tax revenue collected on legal alcohol and renamed the Alcohol Tax Unit.

Next Story: Key Court Rulings Enhanced Prohibition Enforcement