The Repeal of Prohibition

Scroll to read more

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

The Repeal of Prohibition

By 1929, after nine years of Prohibition, many Americans were discouraged. They had long seen people openly drinking illegal alcoholic beverages that were available almost everywhere. They read news stories of murders and bombings in the big cities, perpetrated by organized crime members made rich from bootlegging liquor, wine and beer and smuggling it by land, sea and air.

In Chicago, on February 14, 1929, cohorts of infamous racketeer Al Capone lined up and gunned down seven associates of rival gangster George “Bugs” Moran in what reporters nicknamed the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. The news of the brutal mass slaying shocked the country, including proponents of Prohibition. Meanwhile, Capone held news conferences and dressed in flashy suits at public sporting events. He was taking in as much as $60 million to as high as $100 million a year from bootlegging while corrupting police, judges and politicians through cash payoffs.

The public started having second thoughts about Prohibition not long after it started. As early as 1922, 40 percent of people polled by Literary Digest magazine were for modifying the National Prohibition Act (regulating alcohol, also known as the Volstead Act), and 20 percent backed repealing the 18th Amendment. In 1926, 81 percent of people polled by the Newspaper Enterprise Association favored modifying the Prohibition statute or outright repeal of the amendment.

Just a few weeks after the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, on March 4, 1929, President Herbert Hoover, himself a committed “dry,” took office and right away requested that Congress meet in a special session on a long list of issues. At the new president’s request, Congress passed a bill to create a special commission chaired by former U.S. Attorney General George Wickersham to study what Hoover said was the problem of enforcement of Prohibition and whether repeal was necessary. The new president told his Treasury secretary, Andrew Mellon, “I want that man Capone in jail.” That October, the stock market crashed on Wall Street and so began, amid Prohibition, the Great Depression, the worst economic downturn in the nation’s history.

But Hoover’s decision to appoint a commission to study the problems of Prohibition was criticized as inadequate by Pauline Sabin, the first female board member of the Republican National Committee and a nationally known “dry” advocate. In April 1929, Sabin decided to switch sides and campaign for repealing the 18th Amendment. She was disillusioned with it, having seen many people drinking and flouting Prohibition in New York, notorious for its thousands of speakeasies. She resigned from the Republican committee and launched a repeal advocacy group, the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform. She quickly found that many other American women – who like Sabin once favored Prohibition – agreed with her about repeal. Sabin’s pro-repeal movement caught fire and her organization had more than one million members by 1932.

The Wickersham Commission met over 18 months, hearing testimony in closed session from U.S. attorneys, state district attorneys, high-level police officers, economists, doctors, social workers and labor leaders, and reviewed reports from its investigators, statements from members of Hoover’s cabinet and large amounts of books, papers and surveys.

The 11-member panel released its findings and recommendations about Prohibition in a lengthy report in January 1931. To Hoover’ s satisfaction and praise, the commission unanimously opposed both repealing the 18th Amendment and the return of legalized saloons, once prevalent across the country and run by politically powerful liquor producers. The commission also advised against changing the Volstead Act to permit low-alcohol beer, even with only 2.75 percent alcohol content, and light wines.

But beyond its recommendations, the commission’s findings were bluntly critical of the actions of federal and state law officers during Prohibition, saying the Bureau of Prohibition and other federal agencies got off to a “bad start” and “were badly organized and inadequate” from 1920 to when Congress adopted reforms in 1926. Commissioners said that even after the reforms, “there is yet no adequate observance or enforcement” of the Volstead Act.

One major problem was lack of cooperation from the states. Few states were assisting federal agents in investigating and prosecuting violations of Volstead. Further, corruption was rampant among law enforcement officers in cities and states and among Prohibition agents themselves. Organized gangs of liquor racketeers corrupted local politics through “tribute” payments or bribes to allow the transport of illegal liquor. Added to that was the difficulty of effectively patrolling almost 12,000 miles of shoreline on the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf Coast with many inlets and hiding places for smugglers, about 3,000 miles in the Great Lakes region, plus rural areas with mountains, swamps and forests.

“The facts stated and discussed in the report of the Commission can lead only to one conclusion,” wrote member Henry W. Anderson. “The 18th Amendment and the National Prohibition Act have not been and are not being observed. They have not been and are not being enforced. We have prohibition in law but not in fact.”

The commission cited a series of damning statistics, provided by the Bureau of Prohibition, revealing just how unbridled bootlegging was and the difficultly of controlling illegal liquor in the 48 states. The number of liquor-producing stills seized went from 32,000 in 1920 to 261,000 in 1928. The bureau estimated that 118 million gallons of illicit wine and 683 million gallons of beer were produced in 1930. At least nine million gallons of industrial alcohol meant to be non-drinkable were diverted by gangsters, for cocktails served in speakeasies, in 1930. Meanwhile, the bureau had only 1,786 agents, investigators and special agents. The commission recommended that be raised to at least 3,000 personnel.

But importantly, the Wickersham panel advised Congress and the states to pass a modified version of the 18th Amendment, reducing it to a simple paragraph, giving Congress the right to regulate or prohibit manufacturing, transportation of intoxicating liquors within the United States. It also called for Congress to establish a National Commission on Liquor Control. However, in a suggestion that perhaps concerned Hoover and the drys, the commission said Congress should have the option “to remit the matter in whole or in part to the States” — thus giving states against prohibition the right to legalize alcohol within their borders.

When the Wickersham Commission’s report came out, the nation was well into the Depression. In 1930, unemployment more than doubled to 3.2 million. Some farmers lost their farms, others were affected by crippling droughts. There were food riots, an increase in suicides and military veterans and poor people living in tent cities called “Hoovervilles.” Hoover and Congress struggled to pass urgent bills to aid farmers and provide emergency funds for public works projects. Meanwhile, the Anti-Saloon League, the lobby group most responsible for winning over Congress to pass Prohibition laws in 1919, had lost its clout and could no longer raise funds from the public to pay its bills.

Congress took up some of the Wickersham recommendations in 1932, but the drys in both the House and Senate remained a powerful force. They blocked consideration of the commission’s advice to send a revised 18th Amendment to the states. The drys also obstructed proposals to legalize and tax beer with 2.75 percent alcohol. But many of the drys would be in for a drubbing in the next election.

Just how much longer Prohibition would have remained had the nation’s economy not collapsed in 1929 will never be known. With unemployment high and tax dollars down, many believed repeal would mean new jobs, business expansion and tax revenues. Hoover faced a more than difficult re-election campaign in 1932. He did win his battle against Capone with the gangster’s imprisonment for tax evasion in 1931. Still, with polls showing majority support for repeal, even the longtime dry Hoover had to pivot and declare himself in favor of repeal, to the disappointment of the “dry vote” that was part of his voter base in 1928, when he ran against Democrat and avowed wet Al Smith.

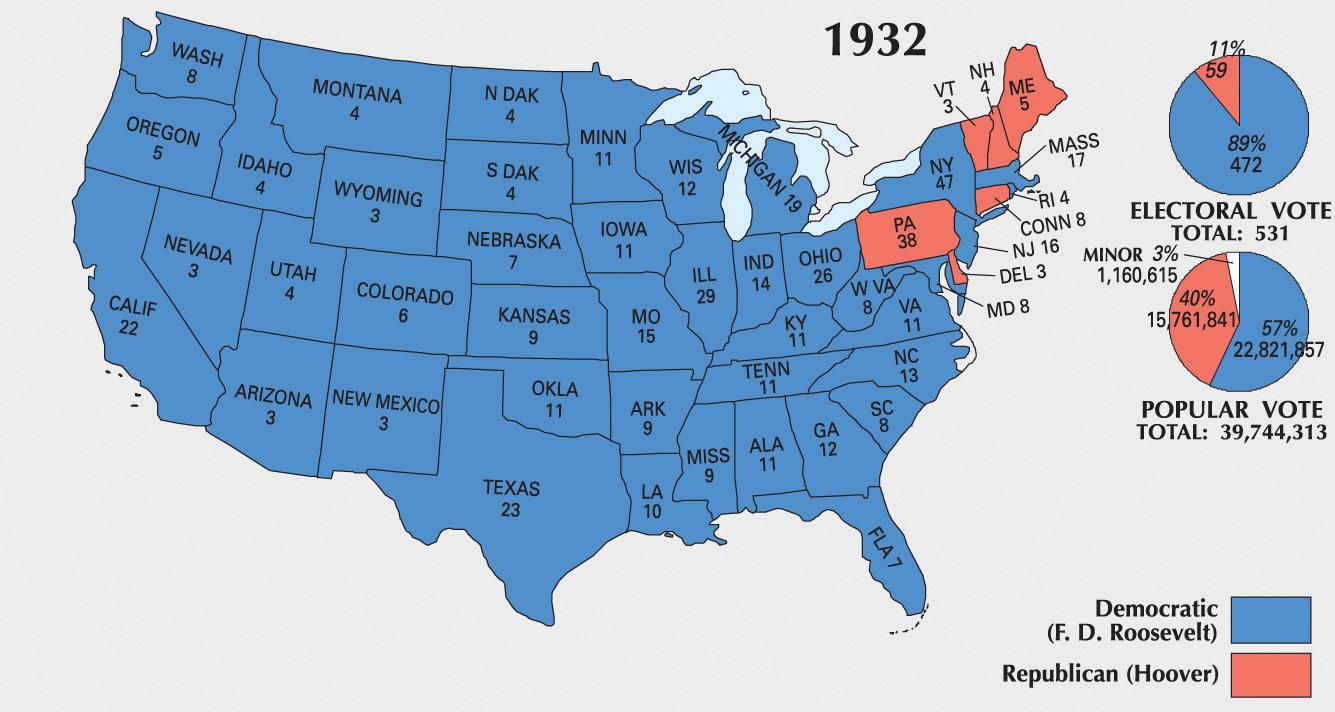

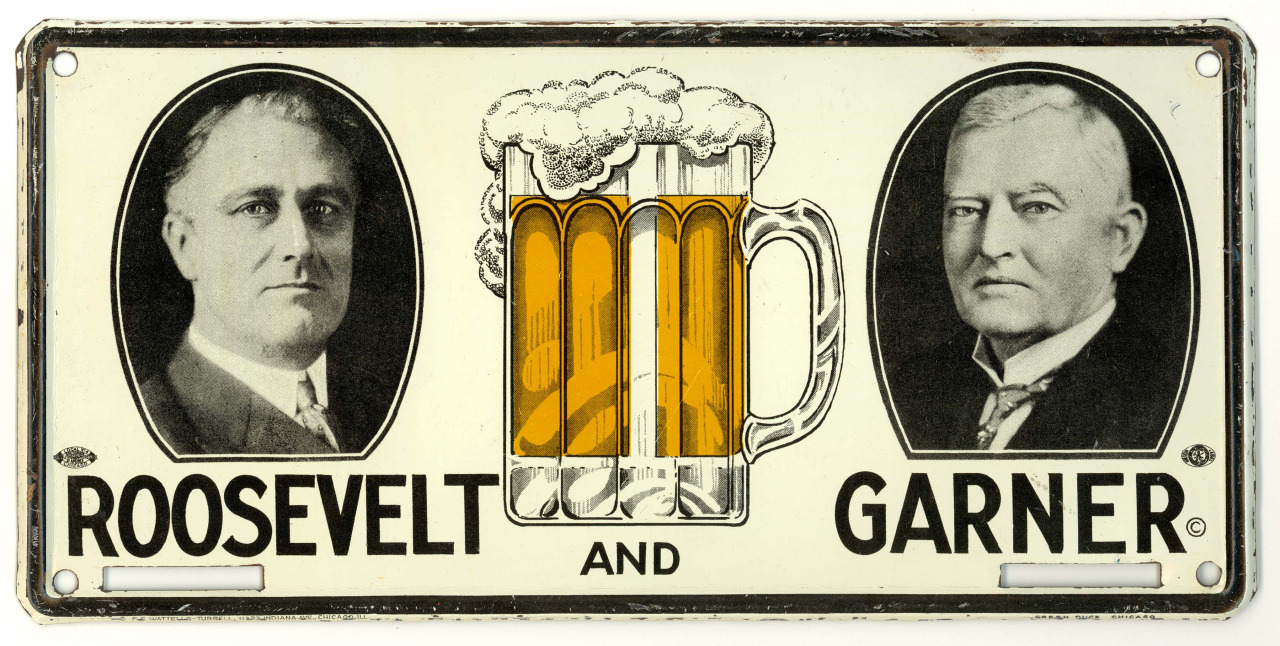

During the 1932 general election, New York Governor and Democrat Franklin Roosevelt (who had vacillated for years on Prohibition) took advantage of both the apparent failures of Republican policies before the Depression and the rising opposition to Prohibition. Roosevelt’s party had a pro-repeal plank on its platform and he campaigned for it, stating that legalizing beer alone could raise “the federal revenue by several hundred million dollars a year.” For Pauline Sabin, repeal transcended party identification. The Republican got her million-strong Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform to endorse Roosevelt.

Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a record landslide – 22.8 million votes to 15.7 million – and voters installed large Democratic Party majorities in the House and Senate. Congress, still in the lame-duck session, started considering a draft of the 21st Amendment that would repeal the 18th. The House and Senate passed it in February 1933 and sent it to the states for final approval. Under the amendment, each state had to vote on the issue by referendum, and if repeal won the popular vote, the state’s legislatures had to appoint and send delegates to a state convention where delegates would vote up or down on repeal. The purpose of that requirement was political — to prevent the Anti-Saloon League lobby and “dry” legislators from bottling up the amendment in the state legislatures.

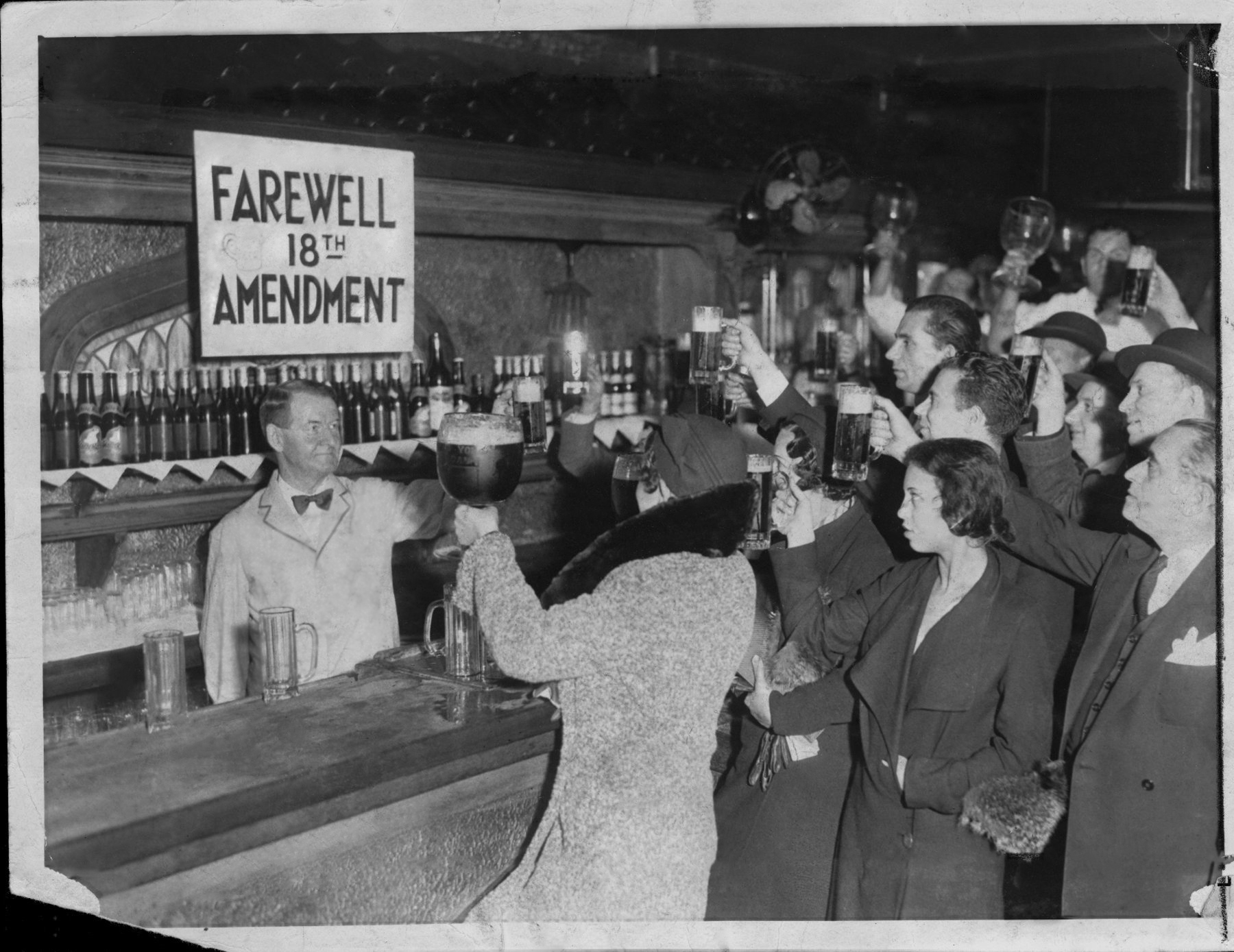

While pundits predicted the state conventions might take years to convene and vote, it didn’t happen. The conventions took up it swiftly and delegates cast their ballots for repeal as if in a race for time. Meanwhile, less than two weeks after taking office, Roosevelt was hosting a dinner at the White House when he remarked to guests, “This would be a good time for a beer.” He wrote a brief message, with language from the Democrats’ wet convention platform, and had an aide take it to the House of Representatives. He asked for a bill to rewrite the Volstead Act to legalize beer with 3.2 percent alcohol content and light wines. Prominent dry leaders made statements to reporters to take a last swipe at Roosevelt’s bill, the Beer-Wine Revenue Act. But the act would serve to elevate national morale by legalizing beer and wine and raise badly needed tax money for the government. Congress passed the act nine days later, Roosevelt signed it on March 22, 1933, and it went into effect on April 7. States that wanted to remain with Prohibition were allowed to. The country celebrated by drinking beer and wine that, while low in alcohol, was finally legal after 13 years.

In the meantime, state conventions, one by one, ratified the 21st Amendment, starting with Michigan. On November 7, 1933, only nine months after Congress sent the repeal vote to the states, Utah’s legislature became the 36th to approve it, the last required out of the 48 to place it into the Constitution. Three state conventions approved it as of December 5, 1933, making it official. National Prohibition was over. The new amendment barred transportation or importation of intoxicating liquors into any state of the United States in violation of the state’s laws. Control of licensing and regulating alcoholic beverages was now mostly a matter of state law. It was the first time in U.S. history that the country amended the Constitution to repeal a previous amendment.

Today, federal law makes it legal to drink beer and wine made at home for personal and family use only. But you can’t distill spirits — hard liquor like whiskey or moonshine – at home. Stills are still illegal, a potential felony crime. If you want to distill any hard liquor, to brew beer or make wine in order to sell it commercially, you need a federal permit from the Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department, and pay the federal taxes on what you produce.